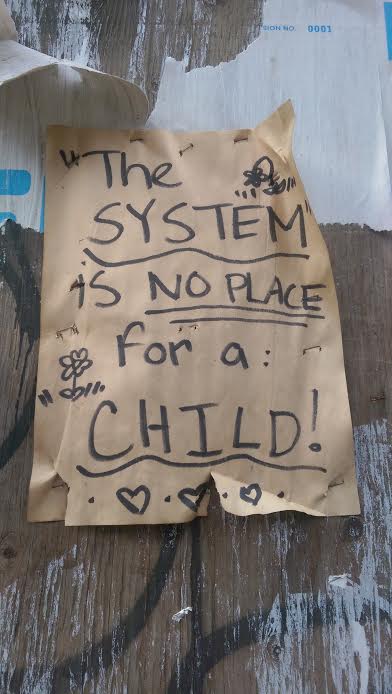

Indigenous youth in care – the continuation of the residential school system in British Columbia

The situation for Indigenous youth across Canada is dire, and British Columbia is no exception. In BC, an Indigenous youth is 17 times more likely than non-Indigenous youth to be placed in foster care by social services. Less than 10% of children in British Columbia are Indigenous, and yet 62% of youth in care are First Nations or Métis. These are some of the disturbing findings of a report from BC’s representative of Children and Youth released in March of this year.

The government of BC is responsible for delivering child welfare services to all children, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous, whether they live on or off reserve. This responsibility of the BC government came into effect in 1951, when the Indian Act was revised to enforce child welfare laws on reserves. This provision of the Indian Act was also a prime reason for the “Sixties Scoop,” the mass dislocation of Indigenous children from their families and communities and their placement in white middle-class Canadian homes. In 1951, there were only 29 Indigenous children in care in British Columbia; 13 years later, the number of Indigenous children in care had risen by, unbelievably, more than 5,000 percent, to 1,466. This government policy of adopting Indigenous children out of their communities has never stopped.

In November 2016, Grand Chief Ed John authored a report at the end of his position as Special Advisor on Indigenous Children in Care. The report issues a scathing critique of BC’s care services for Indigenous youth. John asserts that not only are care services for Indigenous youth systematically underfunded in BC, as well as mismanaged and lacking community-oriented leadership, BC care services also perpetuate the same harms that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified in their investigations of the residential school system.

As Grand Chief Ed John writes, “a bigger and brighter version of the existing children welfare system will not address the concerns or meet the expectations of Indigenous peoples.” In his meetings with Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Nations, Kwakiutl Nation and Quatsino First Nation, he writes the following:

I was advised that a young girl, in line for an important traditional name she was to receive at an upcoming potlatch, was denied access to the potlatch by MCFD [Ministry of Children and Family Development] officials. Seeing this as an act of “insensitivity” by MCFD social officials, representatives at the meeting described the act as one of “cultural alienation” and continued “cultural genocide.”

I was told by the uncle of a young father whose children were apprehended and taken into care by MCFD that, despite the best efforts of the father to comply with the MCFD conditions required for his children to be returned to him, including his attendance at a treatment centre on three occasions, this young father was routinely denied access to his children by MCFD officials. MCFD officials, I was advised, had no intention of returning the children. Nowhere to turn, the young father gave up and in the ultimate act of despair, committed suicide.

I spoke with a couple who, struggling with substance abuse, had six of their children removed. The couple explained how they went through mediation and followed up on their commitments to MCFD to have their children returned, but to no avail. The mother emotionally recounted how she had a new baby born in early November 2015 and was invited by MCFD officials to a meeting at the local MCFD office. When she arrived at the office, her newborn with her, the baby was apprehended by a social worker. Desperation in her voice, she pleaded with me, “I want to have hope. I have waited a long time.”

It should be clear from Grand Chief Ed John’s words and experiences with First Nations communities that the problems underlying the care system and its effects on Indigenous youth are much deeper than any major political party in BC, or in Canada, is addressing. The changes that are needed to keep youth in their families and communities require a radical turn away from colonial policies, and a deep acknowledgement of Indigenous sovereignty. Instead of looking to colonial political parties for solutions, Indigenous communities must continue the long fight for self-determination that our ancestors have laid before us.