Foreign investment is not a working class issue – Universal housing to refuse imperialist survival

This is an edited version of a talk delivered at “The Housing Crisis is Global: Anti-Imperialist Perspectives on the foreign investment myth” panel discussion organized by Alliance Against Displacement and Chinatown Action Group, November 22 2016.

In January 1911, the city of Vancouver expanded its limits eastward to consume the wild and industrial lands around the Hastings Townsite at the Mill. Just months after his property was brought under the legal jurisdiction of the city, a property owner at Hastings Street and Salsbury Drive named William McQueen brought a complaint to the planning department of the City about an ‘Indian rancherie’ – a term that comes from the US that means a temporary camp – the edge of the train tracks between his property and Hastings Mill. Later that day in a motion that did not mention the problematic camp the planning department voted to extend Salsbury Drive over the tracks to join Hastings Street to Hastings Mill, smashing the camp.

This shows us that private property and settler entitlement is not only the foundation of the sense of the housing crisis here, and that people feel disentitled and denied; private property is also the foundation of the displacement and dispossession of Indigenous people. It is carried out following the desires of settlers, and is organized by governments. While the pavement under our feet represents a moment of accumulation, it does not represent the accomplishment of accumulation. Our struggles against these forces of violence continue.

Imperialism and gentrification

Imperialism and gentrification

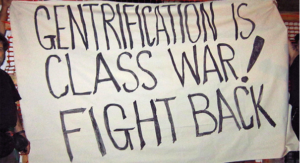

The premise of my talk is that gentrification is a form of imperialism.

Imperialism is a word that different people use differently. I will be using this word to explain a crisis in capitalist economic growth – that when regular capitalist production, the economic production within this system, in Canada for example, hits a limit of growth, imperialism describes the accumulation of resources from outside Canada’s existing production spaces. It’s what BC Premier Christy Clark refers to when she says we have to “grow the economy.”

Outside of capitalist production does not mean outside Canada’s border, but outside the capitalist law of value. Our way of thinking about space as totalized, or as finally constituted and set by the borders of a nation state gets in the way of our understanding of how capital violently pulls every social relationship, every way that we imagine our relationships together, everything that we care about, into the compass and under the control of the law of value and commodity production. The law of value means that the things and rate of production is determined not by what we as a species need to survive but for the sake of the making of profits. It means that production is tied to the potentials for capitalist profits, not the needs of humanity.

Canada’s state apparatus is fundamentally an imperialist state apparatus. The government of Canada bears the burden of funding and organizing imperialist efforts because those investments are typically huge, and no private company wants to or is able to put out all the risk for investment. But those public investments made by Canada benefit private corporations.

The examples of imperialism we normally think of are wars. Canada’s wars in Haiti or Afghanistan – those are examples of imperialism that we typically look to. More recently we’ve looked at resource extraction projects. Canada has publicly subsidized the private profits in resource extraction projects, and their transportation infrastructure, and this is an imperialist act. One historical example is the use of the RCMP to put down the Indigenous Northwest Resistance at Batoche in 1885, using infrastructure that the government underwrote through heavy subsidy and incentives in order to steal Indigenous wealth with the Canadian National Railroad. Another example is the government-subsidized tar sands project that steals Athabasca Chipewyan lands using publicly-subsidized infrastructure. These pipelines are currently being fought all across their proposed routes, including the Kinder Morgan pipeline the federal government approved just hours ago.

Wrinkles in capitalist hegemony

Wrinkles in capitalist hegemony

Gentrification is also imperialist.

Gentrification is part of what geographer David Harvey calls accumulation by dispossession – the gathering of value by direct theft rather than through the exploitative relations of capitalist production. Theorists today use accumulation by dispossession to explain the imperialist theft of resources, lands, or people outside the compass of the capitalist law of value. They use it to describe Canada’s theft of Indigenous lands and resources. But accumulation by dispossession is not exclusive to colonialism.

An original theorist of imperialism, Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote extensively about imperialism as a constant component of capitalist production, said that while capitalism is totalizing – always trying to make a whole out of the world it can dominate – it is never totalized. It never finishes making the world its own. Within the capitalist world there are always wrinkles. These wrinkles in space allow for the growth and development of other kinds of economies and ways of being, even in a world that is dominated by capitalism.

Gentrification exploits these wrinkles in space. Gentrification is a social and economic process that replaces low-income, working-class, racialized communities and their homes and non-capitalist social and resource spaces that they’ve built in these wrinkles. It replaces them with higher-income, professional-managerial, whiter groups and their consumer spaces. Gentrification is not a natural or inevitable process; it is planned and enabled by city (and other) governments for the profit of investors, real estate developers, and entrepreneurs.

In the DTES, capital flight formed a wrinkle that I remember organizing within in the 1990s and early 2000s. Capital flight made the DTES into a wasteland of empty storefronts and abandoned buildings. These were capital-neutral spaces that fostered affective economies of mutual care, where people survived by taking care of each other, not by dependence on wage labour. Alongside these affective economies were illicit economies of drug, sex, and scavenged or stolen goods. These two economies sometimes aligned and sometimes contradicted. They existed because capital flight created these wrinkles in the body of the capitalist city.

It is not an accident that the planning language of gentrification is revitalization: it is literally the Frankenstein-esque bringing back to life of capital that has stagnated, ceased circulating, lay fallow in these buildings and streets that have been abandoned. The dominant presence of Indigenous and low-income people helps depress the value of these non-capitalist spaces because these people are culturally dehumanized and are symbols of urban blight.

We usually think of gentrification as a displacement force that uproots and pushes out low-income, racialized, Indigenous communities for consumers to take their place. It is useful to think about that displacement as facilitating a dispossession – where predator, imperialist real estate developers raid the wrinkle where land and property have ceased circulating. The displacements we see break the non-capitalist economies of the residents, as real estate predators steal and re-commodify the resources – homes and streets – of their economies.

Real estate predators

Real estate predators

Imperialists prey on this dormant, stagnant capital. Predator investors buy up and shutter buildings to drive down land prices further and assemble mass land packages with the gamble that the future will bring opportunities that others can’t foresee. When the massive abandoned Woodward’s department store was scheduled for redevelopment as condos through a public-private partnership, predator investor Stephen Lippman began buying up all the buildings across the street on the 100 block of W Hastings. He bought and emptied them one at a time in order to drive down the prices of neighbouring buildings, until he owned the entire block. He sold them all during the week that Woodward’s condos-sales opened, making millions that he has since re-invested in gentrifying and mass-evicting SRO hotels. On the 100-block of East Hastings, Marc Williams did the same. He bought and emptied out the buildings between the Regent and Brandiz hotels one at a time, until he could assemble the package and make the Sequel 138 condos.

In both these cases the state underwrote, intervened, and incentivized the predator profiteering. Stephen Lippman benefited from the certainty of the Woodward’s condos, which were underwritten by the Provincial government and City height and density bonuses and tax breaks. Marc Williams was rescued from bankruptcy by BC Housing, and the Province poured public dollars into the condos as a public-private partnership for an insignificant number of social housing units. In each case the government declared that these projects were about the ‘revitalization’ of the neighbouhood, not the social housing that was being built there.

Real estate as a wyrd commodity

Why are real estate predators able to dispossess land and housing as they are not able to do with other forms of commodities? The secret is that real estate is a wyrd commodity. A commodity holds value according to how much labour has gone into producing it. But not real estate. Not land. The value of land is based on “expectations of future rents,” not the labour it contains, says David Harvey. This is a cultural production.

Cultural determinants of value are not entirely unique. In the early 20th century, Chinese workers had lower wages than whites because the value of their labour power was depressed by the dominant white race idea that they required fewer calories and less living space than white men. These cultural expectations drove down the wages of Chinese men. But with land, the level of cultural interference in value is nearly absolute.

Imperial culture (possessive investment in settler colonialism)

What are the cultural determinants of land value? I argue that it is imperial culture.

At the beginning of the 20th century, imperial culture was tied very heavily to family. White workers who didn’t have families, who didn’t own land, and who were transient suffered an economic position and a lower social position than those who did. It was that access to culture that pressed most heavily on their desire to be included. It was not the direct demand for land that led radical white working class men to abandon revolutionary struggles with the Industrial Workers of the World in free speech fights in Oppenheimer Park and alongside sex workers at the last legally tolerated sex work district on Alexander Street. What led them to abandon those movements and align themselves with imperial society in the symbolic centre of the city was their desire for families. It was the desire to feel that they were included in that imperial order of sexual and gender norms.

The foreign investment discourse reveals what imperial culture is today. HALT is a Vancouver group that advocates against foreign investment in real estate. Some of the things they say include: “No one born and raised here will be able to buy anything – the next generation will all be renting from foreign landlords who will charge exorbitant rates of rent.” This suggests a continuation of the original entitlement promised to white settlers to draw them to western Canada; the “settlement of the west” that was one of the pillars of John A. McDonald’s confederation national policy.

The foreign investment discourse reveals what imperial culture is today. HALT is a Vancouver group that advocates against foreign investment in real estate. Some of the things they say include: “No one born and raised here will be able to buy anything – the next generation will all be renting from foreign landlords who will charge exorbitant rates of rent.” This suggests a continuation of the original entitlement promised to white settlers to draw them to western Canada; the “settlement of the west” that was one of the pillars of John A. McDonald’s confederation national policy.

They talk about money laundering and gangsterism and shadow flipping. The narrative here is that there is a just and reasonable market that is being interfered with by powerful outsiders.

Also in the narrative is a thread of anti-Asian racism. The anti-foreign investment advocates point to their Asian members to shut down anti-racist critics. They deploy a multiculturalist ideal of inclusion under a framework of expanded Canadian belonging. Regardless of ongoing racism within the symbolic borders of this belonging, the prime problem they look at is foreigners. Nationality is a key regulatory framework that has replaced the biological race ideas dominant in the early 20th century with legal and technical frameworks. While the most important way these frames of difference (and different access to rights and wages) are used are in relation to Temporary Foreign Workers, they are also being used by landlords and wannabe landlords to sort good from bad / respectable from feckless investors.

Paradoxically, the conditions that anti-foreign investment advocates point to as their principles that they want to protect are exactly those imperial cultural forces that make land purchasing in Vancouver more desirable. Imperial cultural forces are constructed of myths and fantasies. There is a fantasy of colonized land as the best investment, which will always appreciate in value. This is a profoundly colonial ideal and fantasy. There is the myth of the permanently stable condition of Canada, which depends on the continued consolidation of settler private property and also on Canada’s imperialist power globally. Finally it is based on the fantasy of Canadian multicultural equality, which obscures what Nandita Sharma calls the neo-racism of temporary foreign worker programs. These myths, fantasies, and imperial cultures do not support a project of ending systems of oppressive power, or racist and colonial divisions of wealth. So these projects should not be ours.

Universal housing: refusing imperialist survival

Universal housing: refusing imperialist survival

Anti-foreign investment reforms are a setback that strengthens local imperialists rather than strengthening our people who are really suffering the housing crisis. They turn what is a working class housing crisis into an investor crisis of competition. The reforms they suggest increase the power of local investors through tariffs, which – coincidentally or not – was another pillar of John A. McDonald’s national policy, which instituted tariffs to protect Canada’s industrial capitalists against more powerful industrial capitalists to the south. These tariffs create preferential market conditions for one group of investors against another based on their nationality.

Instead of looking for the best landlord, I want to suggest that we look instead to universal free housing and refuse the terms of imperial survival. Private property, whether possessed by the mortgage bank, the enfranchised settler, or the landlord, is a technology of imperialism. When I say “we” I mean we who are not materially included in dominant society. We who are not landlords. We who do not feel we belong in Vancouver’s yuppie paradise. We whose human desires for community and security are turned against us with levers of imperial culture. We hate our landlords. We hate the institutional supportive housing we get crammed into. We hate our homelessness. And we desire freedom and security. But we are told that to break from this we should buy land.

Breaking from imperialism means breaking our investments in imperialism – divesting our material lives, our wages, and our dreams from its offerings. I am arguing that we refuse the dreams as well as the realities of private property ownership and the liberal individual security that it promises us. We can instead develop free universal housing by expropriating imperialists as anti-imperialist solution. The state, we can demand, must tax the rich, while we seize apartment buildings to house the poor.

Universal housing will end the unacceptable choice that homeless people are forced to accept between being on the street or being institutionalized. It will redistribute stolen wealth back to Indigenous nations in the form of homes that Indigenous people are disproportionately denied. It will end the unacceptable choice that employed working class people are pushed to accept between precarity under landlords or investing in the imperial structure of private property ownership. It will help us refuse to drain our lives into work; into selling our labour, our days, and our lives for bosses’ profits.

We should fight for free universal homes for all working class and Indigenous people in Canada, regardless of citizenship status so that no body is homeless, so that no body is evicted, so that no body has a blood sucking landlord who produces nothing, whose imperialist dispossession of our communities totally depends on the so-far unbroken cycles of historical dispossession. We can break this cycle by breaking the back of landlordism, of real estate speculation, of imperialism in all its forms; not by implementing tariffs to benefit local investors over foreign investors.

Ivan Drury is a long-time anti-poverty and anti-imperialist organizer. He is a member of Alliance Against Displacement and the Volcano newspaper collective.