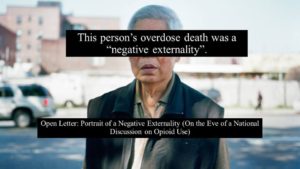

Open Letter: Portrait of a Negative Externality on the Eve of a National Discussion on Opioid Use

By the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs

Originally published November 14th, 2016 on http://capud.ca/index.php/blog/

The most damaging term applied to people who use drugs isn’t junkie, fiend, or pillhead.

The most damaging term applied to people who use drugs isn’t junkie, fiend, or pillhead.

The most damaging term would never be applied to someone in public.

Some of us may have never even heard it ourselves.

This term appears only in government policy papers, research, and grey literature.

This term is “negative externality.”

It’s borrowed from economics and is used to describe a “cost suffered by a third party as a result of an economic transaction.”

In policy, it can refer to negative impacts to either the producer or consumer of an economic good.

In the case of heightened restrictions on prescription opioids, it refers to the consequences of a policy on the consumer of said drugs.

It refers to the death of the opioid consumer.

But you might not ever know that.

Government doesn’t show us whom a “negative externality” looks like.

It looks like me, or it looks like you. It looks like anybody who uses opioid drugs.

The term is as damaging as it is benign sounding.

It’s a term that policymakers use to describe the “unintended negative consequences” of their decision making.

When OxyContin was taken off the market with no planning or consultation with the people using it, many of whom started buying street drugs instead, that was a negative externality. A change that led to people dying of opioid overdose every 13 hours or so in Ontario shortly after it was made. That is a “negative externality.”

When a doctor kicks a patient off prescription opioids as a result of surveillance or a prescription drug monitoring program and that person buys bootleg fentanyl and dies, they term it a “negative externality” as a consequence of some larger policy change.

When a doctor pledges to “First Do No Harm” and failing that then, “I’m going to cut you off your prescriptions” to punish a patient, that’s a negative externality.

When an overdose epidemic worsens because of decisions made by policymakers, by exclusion of the fact that their policy could take more lives, that’s a negative externality.

When an overdose epidemic worsens because of decisions made by policymakers, by exclusion of the fact that their policy could take more lives, that’s a negative externality.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health believe that delisting high-dose prescription opioids is proactive and preventative over a long term time horizon. The move they say, prevents more people using Rx opioids in the future.

In the short term, however, doctors fearful of sanction or discipline for their prescribing practices (see: 86 Ontario physicians cited for overprescribing) pull-back on their prescriptions.

For the people being prescribed opioids, this means the possibility of buying bootleg fentanyl instead.

The people using these drugs right now, whose lives may take an entirely negative turn in the face of these events, who may die as a result of them, are an outcome described simply as “negative externality.”

The public must understand that despite all the media coverage opioid overdose deaths are receiving, our government is not being held accountable about what restricting supplies of prescription drugs can do to the people using them.

They deem overdose deaths as “negative externalities” as a result of another policy change.

These deaths are not negative externalities.

These deaths are cruel and unusual punishment.

They freely get away with using a term so defanged, so banal but yet so unrelenting in its meaning for a person who uses drugs. A term that can be so determinative of somebody’s destiny. A term that crushes those bearing the weight of its structural violence.

It’s not that Health Canada can’t measure impacts of their policy changes (prescription drug monitoring programs, Rx opioid restrictions, etc.) on opioid overdose deaths, it’s that they can get away with NOT measuring them.

Because too many people are unaware of how much life is sucked away when its potential demise is represented in 12 size Arial font as a “negative externality.”

The public needs to know whom a “negative externality” looks like.

Because our government seems unwilling to recognize that their plans to restrict prescription opioids could very well cause a many deal more “negative externalities.”

When it comes to planning our national drug policy, we are all negative externalities.

This week, our federal Health Minister Jane Philpott and Ontario Health Minister Eric Hoskins are co-hosting a conference in Ottawa on the opioid epidemic.

Almost all of us will be “negative externalities” that were not invited into the room to discuss opioid-related drug policy that impacts whether we live or die.

By now, you shouldn’t be surprised that this would be the case.

In decisions that impact our wellbeing to a degree of life or death, once again we are not being consulted.

There will be much talk (if little debate, being that none is allowed) about prescription drug safety in Canada this Friday, November 18th, 2016.

Public, understand that drug safety starts and ends with people who use drugs.

If a drug policy were safe for public health, you’d know it.

On the most basic and essential level, because we’d still be around to tell you about it.

We wouldn’t be locked in a cell, or even worse.

Instead we’re dying in ever increasing numbers.

Those of us surviving their decisions aren’t invited into the room to explain how much things need to change, or how integral we are to a healthy and safe drug policy.

If a drug policy is unsafe, or unsound, we likely weren’t consulted about its implementation.

In September 2016, our organization, the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs, sent a letter to federal Health Minister Jane Philpott to invite her to consult with an advisory board comprised of current or former persons who use opioid drugs.

We received no response from her office.

On the eve of a national discussion that will determine the fates of so many of us, our government has once again, treated our lives as negative externalities.

Once again, we call on our Health Minister to meaningfully consult with the people who live and die by the decisions that she has final responsibility to make.

The way forward for a better drug policy is through our experience, intelligence, and understanding of the policy issues that our Minister has called this conference about in the first place.

Our suggestions for policy improvement:

DON’T measure successful policy just in terms of reducing the amount of prescription opioids in circulation.

DO measure impacts of policy change on people accessing illicit opioids

DO measure rates of people accessing illicit opioids as a result of policy change.

DO Provide evidence-based rehabilitation and concurrent disorder treatments.

DO Provide treatment on demand.

DO Repeal the Respect for Communities Act

DO scale up supervised consumption services.

DO Provide funding for drug user-based organizations.

DO ensure that consequences to people who use drugs are meaningfully considered when enacting policy change.

DO broaden access to methadone and suboxone.

DO decriminalize possession of illicit substances.

DO provide access to prescription injectable opioid treatments (heroin or hydromorphone) for people who have not found success with methadone or suboxone treatments and are in danger of being removed from prescription drugs.

DO expedite licensing for the pharmaceutical manufacture of diacetylmorphine (heroin) within Canada.

Thank you,

Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs