The veil of whiteness – notes on the Black revolts in Charlotte and El Cajon from Vancouver

On September 20th in Charlotte, North Carolina Keith Lamont Scott was fatally shot by the police. Scott was a 43-year-old father to seven children. In the hours after the police murder, thousands of people poured onto Charlotte streets in outrage over yet another instance of police brutality against a Black person. Many of us watched from afar, following the #CharlotteUprising on social media, following the mainstream media’s varied and mostly mediocre accounts.

In the 48 hours following the first protests in Charlotte, Governor Pat McCrory declared a state of emergency and called in the National Guard. Then Mayor Jennifer Roberts declared a midnight to 6am curfew. Charlotte’s streets remained filled with community members who banded together to express solidarity with each other and courage against police dressed in riot gear using tear gas and concussion grenades.

On September 28th, in El Cajon, California Alfred Olango was murdered by the police after pulling an e-cigarette from his pocket. Olango was a 30-year-old man originally from Sudan, who came to the U.S. from a refugee camp in Uganda. He was emotionally and mentally distressed, showing signs of what both his sister and police reported were mental illness. Community members in El Cajon and nearby San Diego led strong protests in the streets after Olango’s murder.

The resistance in the streets of both Charlotte and El Cajon are, above all, expressions of outrage at the waves of violence against Black people that have come to the public’s attention through the Black Lives Matter movement, spurred by the murders of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida in 2012 and Michael Brown in St. Louis, Missouri in 2014.

From Charlotte to El Cajon to Vancouver

In Vancouver, I have watched and listened to reports of these acts of violence, and others, with a lot of grief and horror. As an Indigenous person with two Black siblings who live in the U.S., and Black relatives who extend across the country from Washington state to Florida, I have repeatedly felt this violence to be violence against my own family members. I have repeatedly worried about their safety, their wellness, and their mental health given the stress of constant media reports of police brutality. They are my relatives, my friends, my beloveds, and I feel a tremendous anxiety when I imagine what it would be like to get a call, to find out that someone I love has been shot. And we must remember that not much has changed except the media coverage and our access to sources of immediate footage through cell phone cameras and social media. I mean that these racist and violent attacks against Black people have been the status quo for hundreds of years. If you are recently becoming aware of this racial violence because of the work done by movements like Black Lives Matter, count yourself among the “lucky,” or the pleasantly unaware.

I moved to Vancouver about four and half years ago from the U.S. and a few things stuck out to me immediately. Vancouver seems removed from the dynamics of Black resistance in the States, apart from them, distanced. The whiteness of the place, even though it is an incredibly diverse metropolitan region, was also a real shock. Whiteness in Vancouver functions like a heavy veil. It coats our perceptions and interactions. The best way I can describe how whiteness feels in Vancouver is that it feels thicker, and heavier, than any place I’ve ever lived before. And to be honest, I often feel that it veils my interactions with other Indigenous people, with racialized people, and with Black people specifically.

As a white-passing Indigenous person like myself, I can surf whiteness, or part the veils of whiteness, or play as if the veils aren’t really there. But there are deeply painful emotional, mental, psychic consequences to this. If anything should be pathologized, it’s whiteness. Whiteness has been constituted historically through the denial of Black humanity first through slavery and then through the ongoing attacks against Black bodies that express an inability to perceive Blackness as anything other than a characteristic of the nonhuman. Whiteness has also been constituted through the infantilizing and paternalizing treatment of Indigenous peoples around the world, alongside the concurrent dispossession of Indigenous lands. These forces couple with class-based fears of “the other” expressed through anti-immigrant legislation and violence that is seen in different localities as anti-Asian, anti-Latinx, or anti-Muslim hatred. Whiteness is a social condition that is embodied individually, and is experienced by all of us, no matter where we stand in relation to it. As a condition, whiteness is a socially produced barrier to kinship and solidarity.

So I constantly ask myself, why does it feel heavier and thicker here in Vancouver than in the U.S.? And why do I feel like my relationships with Black people are so affected by whiteness north of the colonial U.S.-Canada border?

I think some of the answers to these questions are embedded in Canada’s historical relationships with, and treatment of, Black people. Over time, Canada’s monied, middle, and aspiring classes have established themselves, in part, through the denial of Black presence. Working class white people also accepted the veil of whiteness by denying Black presence, and all class groups also participated in anti-Asian and anti-Indigenous racism as well. But in contrast to the expressions of anti-Asian and anti-Indigenous racism, in Vancouver today, the sometimes spoken, and certainly unspoken, sense is that “there aren’t any Black people,” or, “there aren’t very many here.” Or, Blackness is an effect of “coming from the States.” Or, a Black person is perceived as an immigrant, and not part of a North American Black community.

I think some of the answers to these questions are embedded in Canada’s historical relationships with, and treatment of, Black people. Over time, Canada’s monied, middle, and aspiring classes have established themselves, in part, through the denial of Black presence. Working class white people also accepted the veil of whiteness by denying Black presence, and all class groups also participated in anti-Asian and anti-Indigenous racism as well. But in contrast to the expressions of anti-Asian and anti-Indigenous racism, in Vancouver today, the sometimes spoken, and certainly unspoken, sense is that “there aren’t any Black people,” or, “there aren’t very many here.” Or, Blackness is an effect of “coming from the States.” Or, a Black person is perceived as an immigrant, and not part of a North American Black community.

Black Canadian identity isn’t recognized as such. Instead, white and non-Black people living in Canada look to the U.S. for recognizable characteristics of Blackness. Perhaps this is why so many Canadians have learned (or are hopefully learning) about anti-Black racism through the Black Lives Matter movement. Black Lives Matter has strong counterparts in Canada, but the movement is rooted in the experiences of Blacks in the U.S. Rather than wondering about the experiences of Black people living in Vancouver, white and non-Black people doubly appropriate the violence in the States, educating themselves through analyses that don’t emerge from the places they’re located in.

White and non-Black people in Canada, and in Vancouver, cannot read Blackness in Canada as a real live presence. It confounds and befuddles much of what the multicultural state is founded upon.

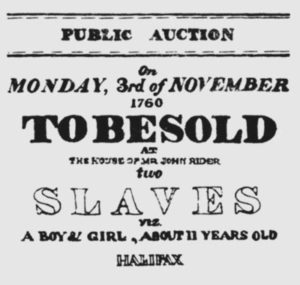

I think this is because Canada’s national mythology established itself against the racial horrors perpetrated in the United States. Canadians define themselves against slavery (though we know there are histories of slavery in Canada), against Jim Crow laws (though we know legal and social discrimination existed here as well), and against the Ku Klux Klan (although the Manitoba KKK had more members than the Communist Party during the depression). Canada’s mythology goes so far as to suggest that Blacks are not only not violently discriminated against in Canada; they don’t exist here, so there really is no problem. These are pure fictions that the condition of Canadian whiteness carries with it.

I think this is because Canada’s national mythology established itself against the racial horrors perpetrated in the United States. Canadians define themselves against slavery (though we know there are histories of slavery in Canada), against Jim Crow laws (though we know legal and social discrimination existed here as well), and against the Ku Klux Klan (although the Manitoba KKK had more members than the Communist Party during the depression). Canada’s mythology goes so far as to suggest that Blacks are not only not violently discriminated against in Canada; they don’t exist here, so there really is no problem. These are pure fictions that the condition of Canadian whiteness carries with it.

In contrast, in the U.S., whiteness was established through the publicly sanctioned and celebrated murder of Black bodies since the beginning of slavery and the establishment of the nation. In the U.S., the condition of whiteness produces a situation in which Black people must be murdered to express the ongoing power, the solidity, the meaning of whiteness. To maintain the power of white settler society in the U.S., the truth of the country’s establishment of its capitalist economy on the backs of Black slaves must be violently eradicated, over and over again.

From Blackness to Indigeneity, from Indigeneity to Blackness

What does this all mean to me, as an Indigenous person living as a guest on unceded Coast Salish Territories?

There is a whole history of differences between the treatment of Black and Indigenous bodies, whether in the U.S. or in Canada. These varied experiences of state violence, of embodied trauma, cannot be weighed. I also don’t think they can be compared, or placed into a hierarchy of pain, suffering, or resistance.

I have been part of uncomfortable conversations with Indigenous people about the relative severity of anti-Black racism, compared to the ongoing brutality waged by the Canadian and U.S. states against Indigenous peoples. There are times when I sense a desire among Indigenous people here in Vancouver to assert themselves against the powerful resistance and solidarity of Black people, to say “yes, but our trauma comes first, colonization comes first.”

There is no first, second or last when it comes to the living legacies of colonialism and slavery that define whiteness in Canada and the U.S. The condition of whiteness creates a situation in which we vie for recognition as those who have experienced the ultimate traumas. But, in the end, who really wants to hold that position anyway?

Instead, I wonder: What meaningful relationships do we, as Indigenous organizers in Vancouver, have with our Black community members, if any? What meaningful relationships do Black organizers hold with us, beyond welcoming Indigenous people to provide an acknowledgement at the beginning of an event? How are Indigenous, Black, Black-Indigenous and Indigenous-Black people represented in our political organizations? Do we hold accountable leadership roles, or do we let ourselves get played, helping to cover the diversity bases? And, finally, how do we push our analyses of colonialism and anti-Black racism into throwing off the veils of whiteness that shroud capitalism – that same destructive force that created our unique conditions in the first place – in order to fight it.