Responses to the overdose crisis must include an end to prohibition

People across Canada are continuing to die at staggering rates from illicit drug overdoses. Advocates have recognized a lack of real action from the government in an overdose crisis that has killed at least 555 people from January until September this year in BC alone – an average of two people per day. Beyond its inaction in response to the overdose crisis, we think it’s necessary to reflect on the critical role of government action in killing people under its jurisdiction in a war on (people who use) drugs — through prohibition.

A brief history of drug prohibition in Canada

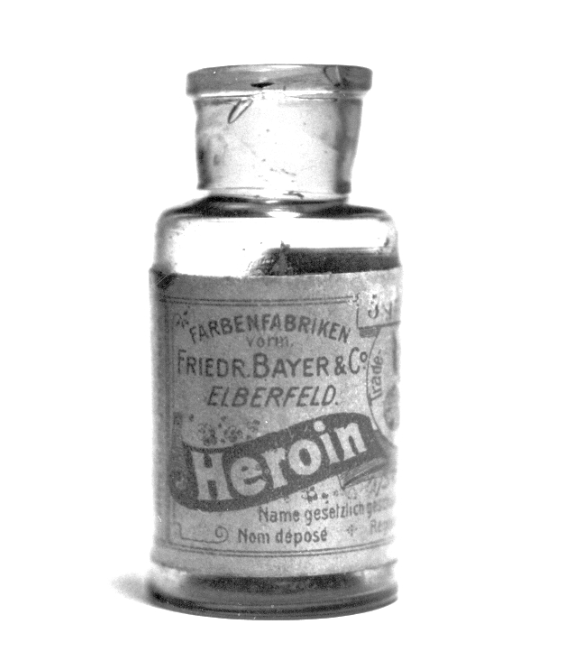

Drug prohibition has been in place in Canada for over a century. European colonizers brought alcohol with them from Europe and also brought liquid opium for pain relief. But it was through federal laws, eventually known as the Indian Act, when Indigenous people were prohibited from selling or consuming alcohol. And so began prohibition, with its beginnings founded in colonial racism.

When Chinese labourers came to Western Canada to work in railroad construction they were paid much less than white workers. And during tough economic times white workers discriminated against Chinese workers, blaming them for the lack of jobs. After the “Asiatic Exclusion League” riot on Labour Day 1907, when white workers destroyed the property of Chinese and Japanese residents and business owners, then-federal Minister of Labour Mackenzie King visited Vancouver to conduct an inquiry into the damage caused. While here, King became aware of the legal use of opioids in Vancouver. Soon after, in 1908, the federal government passed the first official federal legislation prohibiting use of a drug through a law called the Opium Act. This law was: “An Act to prohibit the importation, manufacture and sale of opium for other than the medicinal purpose.” By writing the law this way, the federal government permitted the use of liquid opioid, commonly used by white families, and prohibited the form of opioid mostly used by the Chinese community – crude opium used for smoking. In 1911, the government expanded this legislation to include both morphine and cocaine. If a Chinese person was found smoking opium they could be deported for breaking this federal law. Prohibition was used to discriminate against people racialized Chinese and to give more power to whites and their traditions.

Police and the harms caused by drug prohibition

Prohibition remains a key part of the government strategy to deal with the current overdose crisis in British Columbia. It includes creating community outreach strategies with police, funding drug testing equipment and supplies for the RCMP, and enhancing enforcement of illicit fentanyl traffickers. Keeping certain drugs illegal guarantees an illicit drug market. Governments justify growing their policing budgets to target specific people and communities they associate with these illicit drugs. The segregation and punishment of those deemed least desirable in a capitalist and colonial system (for example, visible homeless who are forced to use drugs in public) is carried out through drug charges.

Efforts to control the supply of drugs play out in our communities through drug stings and anti-gang initiatives. Most recently, the Victoria Police were given $113,000 to police residents of Victoria’s Super InTent City, a key reason given to keep the neighborhood “safe” from an influx of “known gang members” involved in the illicit drug trade. Residents of Super InTent City challenged this narrative. They spoke to the safety they found at tent city where they looked after their neighbors, responded to health crises, and prevented fatal overdoses, and the harm they experienced by police presence and criminalization as a result of the war on drugs. For example, in a three-week period between December 2015 and January 2016 where Victoria saw at least 12 overdose deaths, only 1 occurred at Super InTent City. Numerous lives were saved because people who use drugs could support each other against the dangers created by drug prohibition.

Prohibition forces people into hiding because public stigmatization is compounded by the real fear of arrest, charges, and having a criminal history. As a result, people’s drug use becomes more isolated as they are pushed into environments that are less safe with limited or no support. It is a regular occurrence for people to overdose because they are forced to buy from people they don’t know or whose supply they don’t know after their regular dealer is taken to jail. Arrests also prevent people from accessing safer drug use supplies or Naloxone in jail, and afterwards when they are released with no support. According to a recent study by the St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto, 1 in 10 people who died of overdose in Ontario had been released from prison within the last 12 months. Even when not thrown in jail, regular ‘jack-ups’ and harassment by cops means peoples’ drugs and money get confiscated. Losing drugs and money forces people into desperate and dangerous acts to obtain more drugs or atone for product they have lost. The stakes of being caught in public with prohibited drugs can be immediate and lasting damage that can feel more frightening than the danger of using in isolation, which is death by overdose.

Our governments are avoiding the real problem

Our governments are avoiding the real problem

Recent and proposed changes to provincial and federal legislation have the potential to reduce the harms of the war on drugs. However, under prohibition, these policy changes have limited effects on the ground. Recently Health Canada repealed former Conservative Health Minister Rona Ambrose’s change to prescription heroin allowing it to be prescribed by doctors in cases of “severe opioid addiction.” Currently, the Crosstown Clinic in Vancouver is the only place in North America where prescription heroin is permitted under Health Canada’s regulations. While it’s good to know that we don’t need to fight for this legal change, it’s important to remember that all people using drugs (except for the 200 or so patients in Crosstown Clinic) across the country will not feel any immediate benefits to this recent legal win.

The repeal of Harper’s “Respect for Communities” anti-safe injection site law is necessary so that people can have safer places to use drugs with new injection supplies. But this doesn’t address the problem that people are still using unregulated drugs that could contain anything. Furthermore, once someone leaves the safe injection site, they’re still living under prohibition. And while supervised injection sites are needed to reduce deaths, this means that people can still only use drugs in highly professionalized and specialized spaces. Government spaces are run under the thumb of professional regulatory bodies and funding agencies. Outside these walls, people continue to face the heavy arm of prohibition: grassroots safe injection sites are broken up and people who use drugs are charged with possession and trafficking.

The Government of BC recently announced $10 million, which they say will be spent “to support a British Columbia addiction treatment research and training centre and to fund strategies identified under the Joint Task Force on Overdose Prevention.” With $5 million going to research and education and the remaining $5 million going mainly towards Naloxone and police involvement, it is evident that supporting an end to prohibition isn’t on the provincial government’s agenda.

Lastly, Bill C-244, The Good Samaritan Overdose Act, has not yet been voted on in the House of Commons. This bill would prevent someone from being charged with possession of an illegal drug if they were to call 911 during an overdose crisis. It has the potential to partially mitigate the harmful effects of prohibition by at least decriminalizing the act of saving a life.

Demanding more

We can’t stop fighting only when we’ve increased access to harm reduction supplies, access to Naloxone, and safer places to use drugs. It’s not enough when governments decide to give us the bare minimum. We need to fully end the criminalization of drugs. We need to know what’s in drugs. We need immediate access to detox and treatment, including heroin and assisted treatment, for anyone that needs it. We need to develop effective and accessible treatments for meth and other stimulants. We need to stop arresting people for using drugs. Rather than investing in task forces, more data collection, and public education, we should invest in strong organizations of people who use drugs and listen to them to inform funding and policy direction. Prohibition makes drugs more unsafe. Prohibition breeds stigma. Responses to the overdose crisis need to include an end to prohibition – because it’s still killing people.