The 2018 municipal elections in British Columbia are significant in two ways: one, they are dominated by “the housing crisis,” a term that refers both to the frustrations of members of the professional managerial class who feel entitled to owning a detached house with a fenced yard, and also to the sprawling crisis of life-threatening homelessness. And two, upon the field of “the housing crisis” an array of new political parties and politicians has emerged, each claiming to offer the reform that will solve this crisis of the day.

Of course, there is nothing new about politicians making promises. But following the enthusiasm for Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, a new energy for electoral politics has arisen amongst people on the political left. Purporting a “political revolution,” this revitalized electoral progressivism has been especially energetic at the municipal level, where the model of Kshama Sawant’s election in Seattle is held up as proof that “democratic socialists” can get elected to office. But what they can actually accomplish once they are in City Hall has yet to be shown.

Alliance Against Displacement is not endorsing any political parties or politicians in British Columbia’s 2018 municipal elections. In some cases, we are supporting the slogans that politicians have taken from our movements – like in Burnaby where the mayoral candidate Mike Hurley has adopted a watered-down version of the Stop Demovictions Burnaby demand for a moratorium on demovictions. But we are not enthusiastic about the progressive turn to the ballot box for two reasons:

First, because the only policy reforms that are possible (and these parties are limiting themselves to what they imagine is possible) are inoffensive reforms that slightly improve the administration of capitalism and colonial power at the municipal level without improving life in any meaningful way for our people. These inoffensive reforms have no benefits and all the negative aspects of reformist politics because they adjust the appearance of state power, smoothing relations with the false promise that the system can be made fair with legalistic tinkering.

Second, because politics is happening in the streets, not in City Hall. An important political and economic contradiction in western Canada is that the decades-long turn towards financial investment and speculation has brought incredible wealth for some, and incredible disposability for others. A vast professional-managerial class has grown up to serve the well-heeled investors – both by serving them their luxury goods and by managing the disposable working class and Indigenous poor. In this context, where the majority of the working class is disposable, the politics of City Hall have shrunk to an extremely narrow field of possibility. Political advances can be made, but only by jamming the gears of legalistic possibility, refusing the logic of disposability and the rule of property. Where new political openings emerge, it is because working class and Indigenous people have broken open the corridors of business-as-usual through mass and illegal activities. The electoral circus can only follow politics made in the street – whether the far right populism of the anti-homeless, anti-immigrant, and anti-Chinese mob, or the collective survival struggles of communities organizing against capitalism and colonialism.

In this statement, we develop our critique of the electoral politics of the right and progressive politicians in British Columbia’s 2018 municipal election. We focus on some of the communities where we are organizing in collective survival struggles, but we think these observations and analysis are relevant to communities throughout BC, and to the phenomenon of electoral progressivism more broadly.

In Vancouver the electoral right has a slough of pretenders that are competing for who can marshall the strongest free market slogan: YIMBY, upzoning, legalize housing… The tactic is the same: they want to pour gasoline on the fire of Vancouver’s real estate bonanza so that the flames burn hotter and longer, engulfing more and more people. This supply-side wizardry is based on the myths that the market knows best, that the problem is government regulations that slow market development, and that real estate is a special sort of commodity that will spread to benefit all – if only developers can increase the supply of condos and market rental apartments. But just as producing more cars will not improve public transit, building more condos will not house the homeless.

Progressives compete on a narrow political field

Electoral-progressives also make up a crowded market. The group of four main parties of Vancouver’s electoral-progressive scene, COPE (including the former Team Jean campaign), the Greens, OneCity, and Vision, have agreed to a non-competition clause that has reduced their critique of each other, but have not formed a formal coalition. The non-competition agreement brokered by the Vancouver and District Labour Council (VDLC) in June has guided the number of candidates each group has put forward and has tempered their platforms. “Under the agreement,” a release from the VDLC read, “no party will have more than 4 Council candidates.” The VDLC agreement is supposed to “ensure that parties are free to criticize each others’ records and policies,” but it has had the effect of dampening political differences.

The Vancouver Greens, One City, COPE, and Vision are campaigning separately but on such similar platforms that it would be hard to tell them apart on a blind platform test. The Team Jean and COPE campaign has proven best equipped to differentiate itself, using social movement tactics of performative arrests, slogans and graphics, and old fashioned door knocking and tabling on street corners. But this differentiation has been based on style more than substance. Although each party has its own quirk, they are all calling for modest increases in taxes on estate owners in order to build temporary housing for the poor in the model of the BC Liberals’ institutional “supportive” housing. They are also all in favour of some minor rejigging of the status quo of renters’ rights. Based on their programs alone, there is no good reason for these four parties not to form a coalition. The reason they don’t is because each group is jealous of its brand, and the politics of the electoral-progressive field is so narrow that minor differences of style, “quirks,” or ways of wording platforms end up confusing and dividing otherwise equivalent parties.

Another version of this conflict between free market fundamentalism and inoffensive pacifist reforms is playing out in Burnaby, which is the exception amongst suburban cities for also hosting a Vancouver-style right-wing versus progressive conflict around housing. This dynamic is a result of the years-old social movement struggle in Metrotown against the mass displacement and gentrification policies of mayor Derek Corrigan and his NDP-affiliated Burnaby Citizens Association (BCA) Party. A left field of reforms that would depress and restrain market forces has been opened up by renters in the Stop Demovictions Burnaby campaign (which Alliance Against Displacement helps to organize). Some electoral advocates of inoffensive reforms have seized the opportunity of that opening. The Burnaby Green Party and independent Mayoral candidate Mike Hurley are proposing a watered-down version of the demands mounted by the grassroots; their moratorium on demovictions may rehouse some existing residents but will continue Corrigan’s programme of the gentrification of the majority-renter community in Metrotown, as it leaves the market untouched. Organizers with Stop Demovictions Burnaby unpacked this analysis further in an article published in August calling for “more than a moratorium” and explaining the need to keep organizing against evictions in the streets.

Chasing moral panic votes

In Surrey the number one election issue is “crime,” which means politicians across the spectrum are making promises to increase policing, while feeding into a racist moral panic around public safety. In this election the moral panic around crime and homelessness are connected, with homelessness subsumed into the discussions of crime as a “social problem,” not an economic or political problem. Both racist anti-gang policies and poor bashing anti-homeless policies tend to give rise to pro-cop responses. In Surrey, the political field on “crime” is nearly indistinguishable between the new electoral-progressive Proudly Surrey Party, which is promising increased spending on more police officers through the creation of a new municipal police force, and the ruling Surrey First Party, which is promising increased spending on more police officers and a referendum on a new municipal police force. There is no progressive-electoral party (in Surrey or anywhere in British Columbia) that is proposing to defund the police, fight the moral panic, and focus efforts on fighting the political conditions inherent to capitalism and colonialism that produce poverty and alienation.

A moral panic around “safety” and “crime” is also the focus of elections in many other smaller communities, where the most potent symbol of social disorder is homelessness. The broader housing crisis disappears in the moral panic that engulfs small town electoral debates about homelessness. When CBC radio interviewed mayoral candidates about Anita Place tent city, the conversation was all about crime, drug use, and the mental health of individual homeless people. They didn’t talk about housing affordability and poverty at all. Several candidates did mention the Federal government’s housing first policy and supportive housing, but as strategies to address mental health and addictions rather than the housing crisis. In most cases, the choice in small town elections is between those politicians who cater to the anti-homeless mob and, when we’re lucky, a small group of reformers who advocate for policies of treatment, regulation, and control of homeless people in institutionalized “supportive housing” buildings. Like in Surrey, the political field of these elections is so narrow that the discussion is shaped around the moral panic. The election as a totality further dehumanizes homeless people, pathologizing them as individuals, while obscuring the social and historical contradictions of capital that are making people homeless.

Inoffensive reforms for the servants of the Professional-Managerial Class

The version of the “housing crisis” that is dominating BC’s 2018 municipal election in urban centres is one that focuses on the interests of the most politically and economically important class – the professional-managerial class (we’ll use the acronym PMC for a shorthand). The PMC is made up of engineers, financial planners, corporate brokers, academics, social service managers, middle-level administrators, and other jobs that facilitate the circulation of commodities and manage social organization to stabilize the living world around capitalist production.

Over the last 30 years, the PMC has grown because of the transition of the economy of western Canada from a hybrid of resource extraction and manufacturing to one that scholars refer to as “financialized,” where finance, insurance, and real estate have become more important than manufacturing. In this new situation, which has been produced by a collaborative effort of all political parties, making an attractive investment climate is as important as promoting the “liveability,” safety, security, moderate climate, and good-times of southern British Columbia. City governments play an important role in administering the social life of this new economic order but are caught in a bind because their ability to affect political and economic problems is quite limited.

Vancouver has been particularly hard hit by the financialization shift. Under eight years of rule by Vision Vancouver, the city has been turned into a yuppie paradise. This jarring, alienating shift has made life good for the PMC, and for many legacy property owners who Mayor Gregor Robertson referred to in an interview in October on CBC’s Early Edition as “winning the lottery.” But the vast numbers of servants of the PMC have been neglected. This gap, which some politicians are referring to as the “missing middle,” has meant that in the 2018 Vancouver election there seem to be some openings for inoffensive reforms that can benefit the social groups that the PMC depends on to make the city “liveable.”

Since the 1980s, the services employment sector has increased from less than 40% of the Lower Mainland workforce in 1981 to 78% in 2012, with the great majority of service work concentrated in Vancouver. Service work is a broad definition, ranging from restaurant and retail work to secretarial work to nursing and social work. Some service workers serve the PMC their lattes and advise them on their $400 raw denim, and others police the poor to help keep streets safe. For years, under the majority rule of Vision Vancouver, the interests of the PMC were crudely prioritized, without much attention to the lives of their servants.

If passed, the inoffensive reforms proposed by the four progressive parties (the Four Progressives) are supposed to ease the cost of living and lessen the likelihood of displacement for the servants of the PMC. They might make a bit of a difference for the more well-paid and secure layers of the servants, but for the majority, and the most vulnerable to displacement, they won’t really help. And the differences between the parties that make up the group of four basically amount to attention to different levels of the servant class. Vision, OneCity, and the Greens are focused on increasing the supply of market rental and cheaper condo housing, and COPE is focused on moderating rents. Notably, even the tax reforms of the group of four focus on consumption taxes (including property taxes), not taxes on production like the business taxes that the BC Liberals cut by 60% during their 16 years in office in order to attract investment.

The inoffensive reforms of the Four Progressives are not the same as postwar-style social democratic reforms that subsidized the cost of living and wages for white workers; they are a dim echo of social democracy. The service workers that employers consider “unskilled” are too easily replaced and too non-unionized to effect the sort of pressure that industrial workers did in the 1950s. Plus there is the broader problem that Canadian capital is contracting rather than expanding and bosses are less eager to share their profits than they were in the years following World War 2. The politics of the Four Progressives is a louder and clearer version of the politics of the BC NDP, which promised to “level the playing field” for local condo and home buyers with an anti-foreign investor tax. But the NDP’s reforms arguably only benefited poorer sections of the relatively wealthy PMC themselves.

Shining Vancouver’s Reconciliation Brand

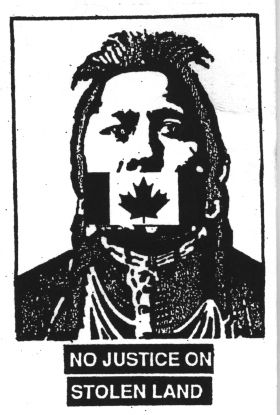

The Four Progressive parties also make some overtures to Indigenous peoples, some using language like “decolonizing” the city. Most of these gestures perfect Vancouver’s Olympics-era “4 host nations” reconciliation brand. Beginning with the 2010 Olympics, VANOC and the City of Vancouver used Indigenous peoples and cultures to brand the city differently from other Pacific Northwest destinations in the United States. In 2014, Vancouver declared itself a “City of Reconciliation,” raising poles and renaming plazas as Indigenous homelessness skyrocketed, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the broader homeless population.

The limits to Vancouver’s reconciliation as a brand are visible in the poverty and homelessness it produces for Indigenous people. Reconciliation in the form of City-organized recognition is appealing, particularly when it means taking out white supremacist colonizer names like Trutch Street, but it is not decolonizing when a colonial government (even a “democratic socialist” one) replaces the streets named for outmoded villains with ones stamped with the era of Reconciliation Inc.

More complicated (and less clear) are the policies from COPE that promise “reconciliation with substance” and OneCity that promise “Indigenous justice.” These policies combine the parties’ inoffensive reforms about housing with a politics that recognize that “the current housing crisis comes after a century of dispossession and displacement for Indigenous people” [One City] and that “this year the percent of homeless people who are indigenous increased from 30% to 40%, while making up only ~2% of the population” [COPE]. Efforts to respond to Indigenous homelessness through a lens critical of Canadian colonialism should be welcome. But do the COPE/OneCity promises live up to the rhetoric? It’s hard to say.

One City says they will address Indigenous homelessness by “offering city-owned lands to Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations for non-profit housing.” It is not clear what this “offering” means exactly. Are they offering management of hypothetical buildings to local nations? A land lease offering like Vancouver used to give housing co-ops? After “offering” land to local Indigenous nations, who would build the housing that might go there? OneCity talks like they are offering to return the title of land to Indigenous nations but don’t say so clearly or explicitly. They also don’t say how much or which land they would offer.

COPE’s plan is equally performative and vague. In their platform COPE says, “The City should work with host nations to create land trusts, restore land to them.” Even this brief passage is contradictory because land trusts do not surrender title to Indigenous nations. In 2016 the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam nations, through a corporation they formed called MST Development Corporation, in partnership with the Federal Crown Corporation Canada Lands Co. purchased the 38.8 acre Jericho Lands for $480 million. In the language of Reconciliation, which is written through the frameworks of white Canadian race ideas and multiculturalism, this massive land acquisition is a return of lands to Indigenous people. But if we think of colonialism as about land relations and capitalist versus Indigenous economies, with Canada’s colonial-economic power of property as the foundation of colonial rule, then Indigenous nations buying and holding fee simple property for investment and economic development in the Jericho purchase represents the investment of three Indigenous band councils in Canada’s property economy.

Given that the MST Development Corporation is currently the vehicle that the three local nations have developed to organize their property and housing projects, it is puzzling that neither COPE nor OneCity mention the Indigenous corporation. Do they plan to work with MST? Or to ignore it and force the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh into a new housing and land body created by the colonial government in City Hall? Reading their platforms, it seems more likely that neither of them have thought it through that far. Neither COPE nor OneCity have talked about their Indigenous Justice or Reconciliation with Substance policies very much. Instead, they prefer to stick to their inoffensive reforms that do not highlight colonialism or the impossibilities of ending colonialism within a settler colonial parliament, or ending colonial property relations that force Indigenous nations to get their lands back by buying them.

And despite COPE acknowledging the dire situation of Indigenous homelessness, other than their plan to build 2,000 units of temporary modular housing, they offer zero solutions that would specifically affect urban Indigenous people. It is a big leap to assume that local band councils will prioritize or are able to respond to homelessness for Indigenous people who are not from their nations. There are also Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh people who, for so many reasons, have tenuous or severed relations to their communities. Overall, COPE and OneCity’s attempts at speaking to a form of decolonized city hall politics (an oxymoron if there ever was one) stop severely short of addressing the realities of the majority of Indigenous people living in Vancouver.

City versus Country

British Columbia’s rural and small town class structure is a bit of a different animal. Here, the usual financial investment core of the turn to financialization is buttressed with the unbroken, even accelerated, importance of resource extraction. Logging, mining, gas and oil extraction, and fisheries are the other pillar of BC’s economy and many of the investor offices in downtown Vancouver prey on Indigenous peoples’ lands to the north and east in the same way that they prey on the lands of colonized and formerly colonized peoples in the global south. This dynamic creates a cultural and economic gulf between city and country.

In places like Nanaimo, the class equivalent of the PMC is the resource worker, many of whom own homes but are feeling old complex pressures and insecurities common to boom and bust industries that use up workers’ energies and discard them just like they do the land. The rural and small-town economy puts the propertied working class and extraction industry contractors directly in conflict with Indigenous peoples defending their lands and non-capitalist economies. In the city, investors and service workers are a step insulated from the colonizer conflict that non-Natives experience in small towns, where anti-Indigenous racism is smoothly translated into anti-homeless hatred. In these places there is less space for inoffensive reform and more of a populist attraction to far right pandering, amorphous moral panic, and undisguised hate.

Being an offensive opposition

The inoffensive reformers are preferable to the free market fundamentalists, even though neither are taking steps towards resolving the housing crisis in favour of working class and Indigenous communities who are experiencing it as violence against their bodies and communities. There are three good reasons to step past the narrowness of the electoral field and embrace politics that offend our enemies in government, business, and the professional-managerial class:

First, because we have decades of political retreat to overcome and a tremendous amount to learn together. We cannot afford to handcuff our imaginations, our critical minds, and our desires to what electoral strategists decide are winnable, pragmatic, inoffensive reforms in an electoral contest. We must discover and tell the truth.

Second, because the inoffensive reforms and blocs of progressive electorates are inadequate to the immediate material needs of our most vulnerable communities. A character of these inoffensive reforms is that politicians (even the ones that emerged from our community organizing) lie about how much they can do. For example, COPE presents a “rent freeze” as a solution when more than half of us are already paying well over 30% of our incomes to rent; they propose a ban on renovictions, but the reality is that the majority of evictions are for failure to pay rents we cannot afford. If we limit ourselves to organizing around elections on these inoffensive and inadequate reforms then we will not build the organizations we need to act outside the law, and we will not understand what we really need to do.

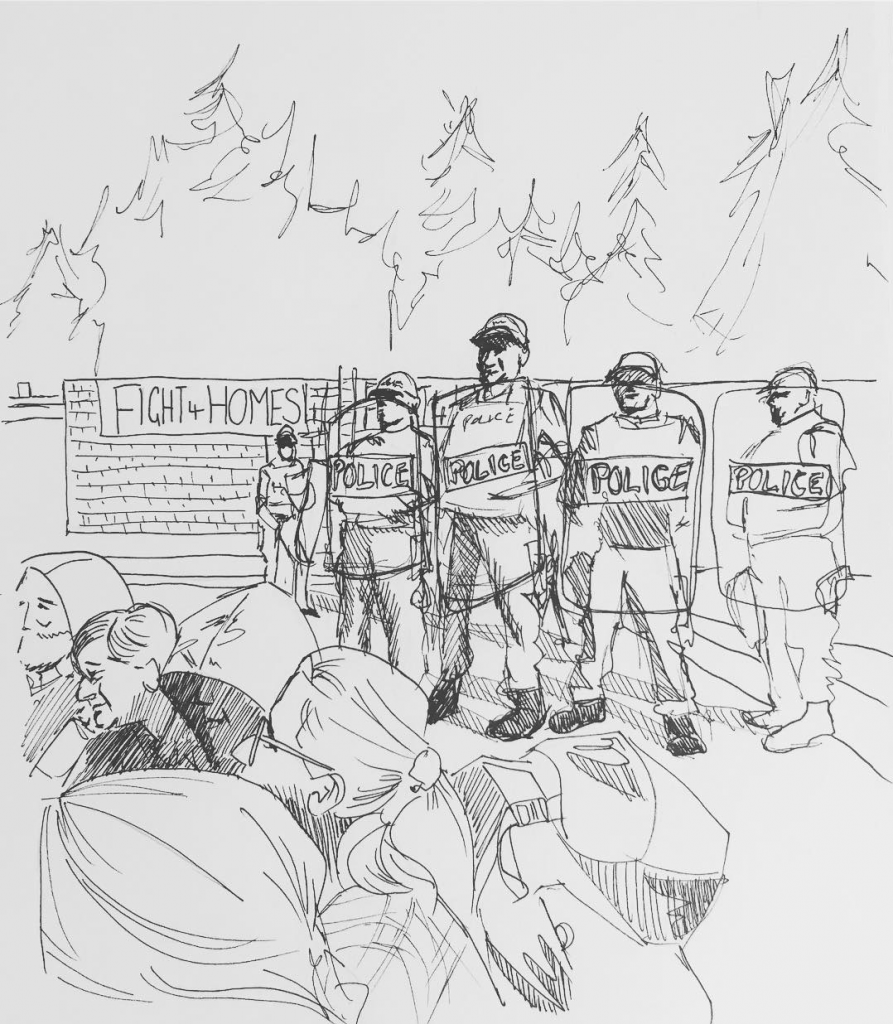

Third, because within the current post-social democracy context, even the most “inoffensive” reforms cannot be realized by politicians in the absence of strong social movements. For example, in Seattle this summer, City Council passed a corporate tax to fund programs for the city’s homeless, then repealed it a few months later under pressure from Amazon and Starbucks. Progressive civic politicians tend to say that they want to work with social movements, but also tend to demand that social movement groups subordinate their politics to their inoffensive electoral policy reforms and distance themselves from groups that they consider to be too radical.

When the BC NDP attacked the tent city in Saanich with naked police force, harassing and denouncing homeless residents and radical organizers in our group, not a single progressive politician in Vancouver or Victoria spoke out against them. When the police attacked and arrested us as criminals in the Nanaimo Schoolhouse Squat, the silence from progressive quarters was deafening, and some people working on electoral campaigns even used the opportunity to differentiate themselves from our action to show that they respect property. It appeared that their election, and their coziness with the NDP government, was more important to them than defending and identifying with the offensively oppositional social movements they will need in order to actually carry out their inoffensive reforms should they be elected.

Where politics really happens

In 1920, anti-capitalist groups from all around the world met in the still-newborn Soviet Union for a congress that grappled with a number of political questions, including how revolutionaries should deal with parliaments. They made some observations that are helpful still today. They found that groups that prioritized getting elected above their political principles “resulted in the reign of Social Democracy’s so-called minimum program and the transformation of the maximum program into a debating formula for an exceedingly distant ‘ultimate goal’.” These parliamentary groups stopped building toward revolution; instead, they turned revolutionary slogans into empty rhetoric. And immediate reforms, which had been a tool for introducing revolutionary political ideas to the masses, became the end goal.

The congress resolution read, “parliament today can under no circumstances be the arena of the struggle for reforms, for improvement in the conditions of the working class [because] the centre of gravity of political life today has shifted irrevocably beyond the limits of parliament.” The parliament and the city hall is the space where different factions of the capitalist class – in our case, this includes the professional-managerial class – haggle over which technique is best to manage the contradictions and periodic crises that have emerged in society.

City hall chases the politics that are being made elsewhere, in the streets, apartment buildings, tent cities, mountains, rivers, and workplaces where the people themselves challenge the existing order and create a different one with our own hands. These political spaces are certainly contested. In Surrey, for every person demanding the abolition of the police there are 10 calling for more cops. In Nanaimo, where homeless people fight against the sanctity and rule of property as a threat to their very lives, far right mobs rally in the hundreds and threaten to assault homeless people and women organizers.

These are the spaces of politics that will remake our world. We cannot afford to ignore them because, if unchallenged, these will be the spaces from which a far right menace will rise. The self-activity of the displaced and dispossessed, the evicted and homeless, reveal the true workings of capitalist and colonial politics. These are not fringe, declassed people; they develop the cutting edge of a critique that we need in order to make a new social order. The revolution is not in changing the guard at city hall, it is not simply formally “political,” it is a social revolution, and it is happening in the streets.