The spring of 2018, apparently, is the season of housing policy reform. The Trudeau Liberal government has released the blueprint for its National Housing Strategy, which is still, incredibly, indefinite about how many low-income accessible social housing units their $20-billion plan will build. The BC NDP government has set sail its Rental Housing Task force by promising to represent the impossibly contradictory interests of both landlords and tenants. Advocates and community groups – many of which receive their scant funding from these very governments – have lept on the opportunity to feed their own policy reform positions into the yawning maw of “housing crisis” discourse. The result of all these policy reform discussions will inevitably be measured in government and Party approval ratings while ensuring that the astonishing mass of evictions continue.

The spring of 2018, apparently, is the season of housing policy reform. The Trudeau Liberal government has released the blueprint for its National Housing Strategy, which is still, incredibly, indefinite about how many low-income accessible social housing units their $20-billion plan will build. The BC NDP government has set sail its Rental Housing Task force by promising to represent the impossibly contradictory interests of both landlords and tenants. Advocates and community groups – many of which receive their scant funding from these very governments – have lept on the opportunity to feed their own policy reform positions into the yawning maw of “housing crisis” discourse. The result of all these policy reform discussions will inevitably be measured in government and Party approval ratings while ensuring that the astonishing mass of evictions continue.

The practical limits of today’s housing policy reform proposals recall the centuries-long theoretical debate that communist leader Rosa Luxemburg termed, “reform or revolution.” In her 1899 article of this name, Luxemburg begins rhetorically, “At first view, the title of this work may be surprising.” She asks – do earnest reformers really oppose revolution, and do revolutionaries really oppose reforms that will alleviate immediate suffering? “Certainly not,” she answers. There is a link – she says – between reform and revolution. “The struggle for reforms is its means; the social revolution, its goal.” The question, then, is whether a particular reform is a means to a revolutionary ends – whether the reform builds the power and consciousness of oppressed people or disorganizes our independent power and misleads us into a dead end.

The whole litany of reforms coming from the Federal Liberals, the BC NDP, and those who are eager to enter into earnest policy reform are the latter – which Luxemburg calls “revisionist.” These reforms call for people being evicted to homelessness to ultimately accept our fate in the name of what is practical for politicians and professional legal advocates who happen to hold power today. They want us to renounce the movement against property and trust our fates to hypocrite politicians; to give up the struggle for our own power and self-determination. Not only are these false reforms a dead end (is it even a reform if it does not stop suffering?), they are not even justifiable as the “practical” solution.

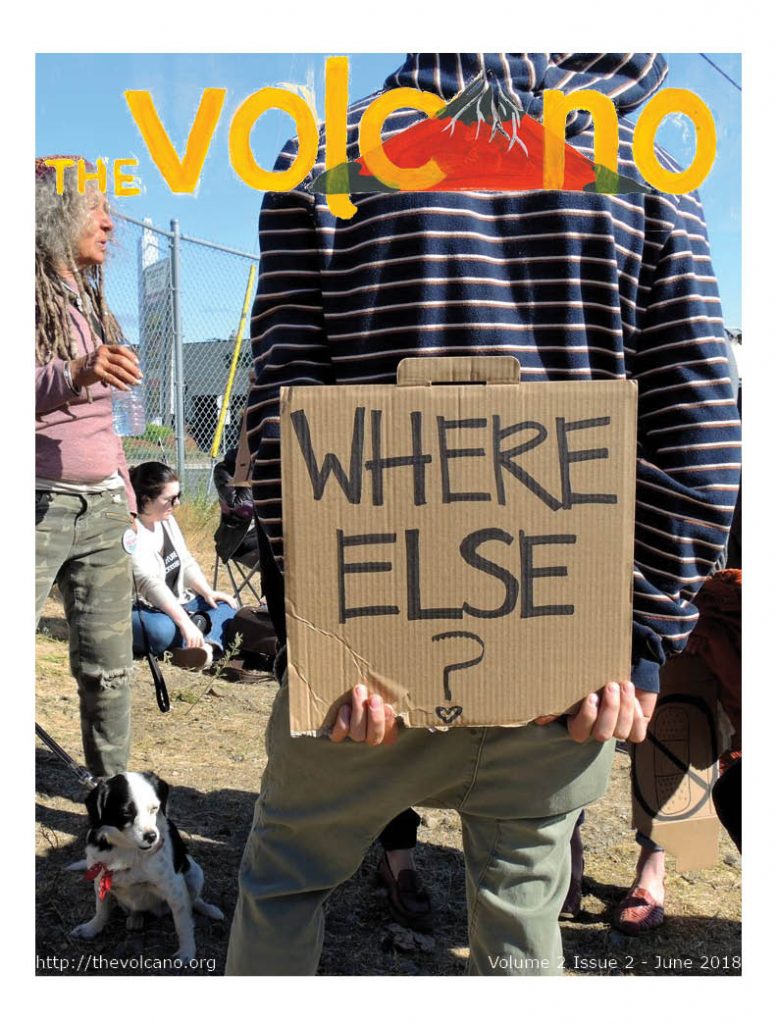

Today some people in BC are organizing around non-state, people-power solutions which create hope for radical change. May 29th was the deadline the City of Nanaimo gave about 60 homeless people to vacate the city-owned lot they had made their home and branded Discontent City. In response, homeless residents of the camp called out for support and at 8:30am when the City’s intimidating trespass order became active, they were joined by homeless people from across the water in Maple Ridge’s Anita Place Tent City and a hundred local working-class and Indigenous people. The anti-eviction rally filled the gates of the tent city and chanted “homes not jails! Homes not police! Homes not displacement!” and cheered together. Faced with the organized and unified people, the City of Nanaimo backed off. The Discontent City defence rally was a sign of another, uncompromising way of defending our communities that builds – rather than gives away – our power to win the reforms we need.

As “reform season” continues – and gets louder in the lead-up to BC municipal elections – let us not be bamboozled by the promises of politicians. And let us not limit our imaginations of what is needed to what self-interested political parties tell us is possible. Rosa Luxemburg’s call to action is not for reform or reason within the legal bounds of property, but for our people to be bold and collectively take what we need to survive. She is right. To survive this nightmarescape of eviction and homelessness we must develop the bravery to think revolutionary thoughts, and in our day-to-day lives we must build our movements around people not protected by colonial bourgeois law. We can push back police threats of displacement and we can break the back of private property, but not if we limit ourselves to vapid, deferential reform.