Not sorry for raiding bathhouses nor brothels – The limits of Trudeau’s LGBT apology legislation

Transcripts of speeches by Gary Kinsman, Tom Hooper, Ron Rosenes, and Angela Chiasson

In December, the Liberal-led parliament passed legislation that followed up on Prime Minister Trudeau’s apology for Canada’s historic criminalizing persecution of lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender, and queer (LGBT) people and communities. This legislation, Bill C-66, the Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act, clears the criminal records of some of those who Canada convicted of certain same-sex offences. Like much of the politics the Trudeau Liberals have implemented, Bill C-66 makes for a better soundbite than legislation.

On April 18th, historians, LGBT activists, and community members criminalized under Canada’s former anti-LGBT laws held a news conference to make public the brief they assembled for Canada’s Senate on the flaws they identify in Bill C-66. Their critiques revolve around 2 major limits of the legislation: that it does not expunge the criminal records of those most often arrested under coded anti-LGBT laws – particularly those arrested under bathhouse and brothel laws, and that it could destroy the records of anti-LGBT arrests, erasing critical documents of LGBT history.

The Volcano is grateful to reproduce transcripts of presentations from LGBT historians Gary Kinsman and Tom Hooper, survivor of Toronto’s 1981 anti-LGBT bathhouse raids Ron Rosenes, and Angela Chiasson of the Criminal Lawyers Association, who spoke as an individual. Watch the video of this entire news conference here.

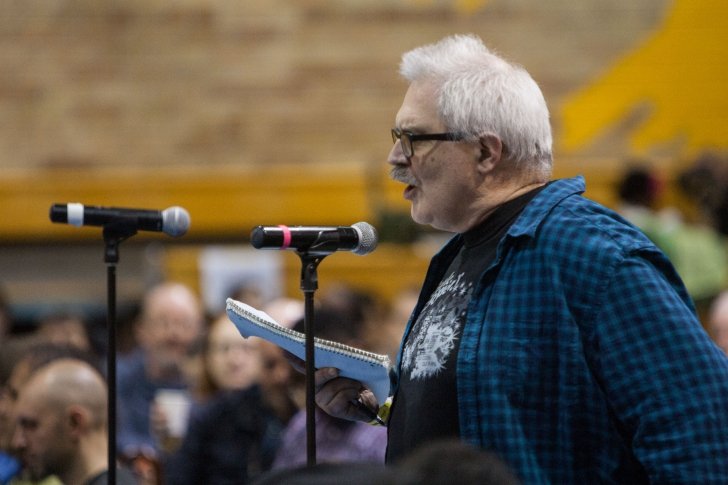

Gary Kinsman, LGBT historian and activist

Bill C-66 was central part of the apology that Justin Trudeau announced last November 28th in the House of Commons. It’s a central part of the apology because one of the major aspects of the oppression of LGBTQ people that was being apologized for was the criminalization of our consensual sexualities. I’m here speaking on behalf of a group of four historians. What is central to defining a historically unjust conviction is that it was the criminalization of consensual LGBT sexual and gender practices. That, for us, is what is core to defining what is an historically unjust conviction.

There are major limitations to Bill C-66. If it goes forward without amendment, it’s going to be fundamentally flawed. We’re only going to be able to talk about some of the limitations of the Bill.

The first and most important thing is that only a small fraction of the offenses that actually affected LGBTQ people who were convicted are covered in Bill C-66, which needs to have a much more expansive list of offenses. Also, the age of consent provisions within Bill C-66 are discriminatory: they export the age of consent of 16 into the past, before 2008, setting up discriminatory practices toward people who engaged in LGBT sexual practices prior to 2008. Finally, it could lead to the destruction of really important historical documents that are an important part of our history.

We are very pleased, as the group of four historians, to be able to present to the Senate Committee today. We were denied the right to both make a submission and also the right to give a presentation when the House of Commons was discussing Bill C-66. But we do want to point out that most of the LGBTQ, trans, and two-spirited groups that presented briefs have been denied the right to present before the Committee, as well as all of the sex worker advocates who approached the Senate Human Rights Committee; so there’s a lot of voices that have been excluded from the proceedings. These need to be listened to—especially the concerns of sex workers around the historically unjust convictions they have faced and also the major concerns raised around the high level of convictions and prosecution of people for HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

Tom Hooper, LGBT historian

As a historian of the bathhouse raids, I was delighted to hear the Prime Minister’s apology in the House of Commons to LGBTQ2 Canadians. He specifically mentioned both the bathhouse raids and the bawdy house law in that apology, so you can imagine how disappointed I was to learn that those were merely eloquent words from Justin Trudeau. Bill C-66, introduced the same morning as his apology, excludes the bathhouse raids.

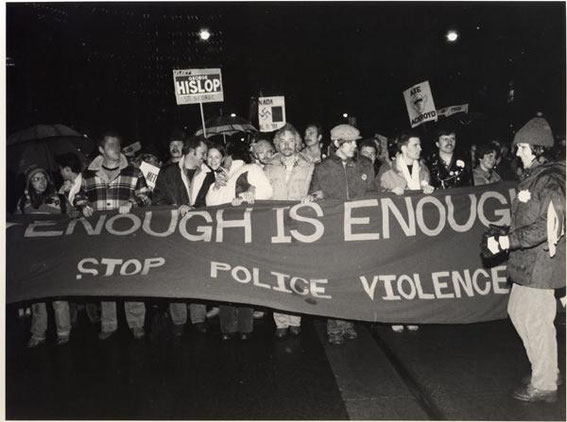

[There were] 38 different bathhouse raids across Canada from 1968 to 2004. In this so-called era of decriminalization, more than 1,200 men were charged under the bawdy house law, simply for having consensual gay sex. The Supreme Court has ruled that the bawdy house law has also unjustly made sex workers unsafe. Given the historical connection between the struggles of sex workers and LGBTQ2 people, we believe they should also be included in Bill C-66.

Ron Rosenes, survivor of the 1981 bathhouse raids

Thank you and good morning. Let me begin by saying that on the night of February 5th in 1981—a night that really remains seared in my memory, despite valiant efforts to put behind me what occurred—I found myself at the Roman baths on Bay Street, at a club for men seeking to meet other men for consensual sex.

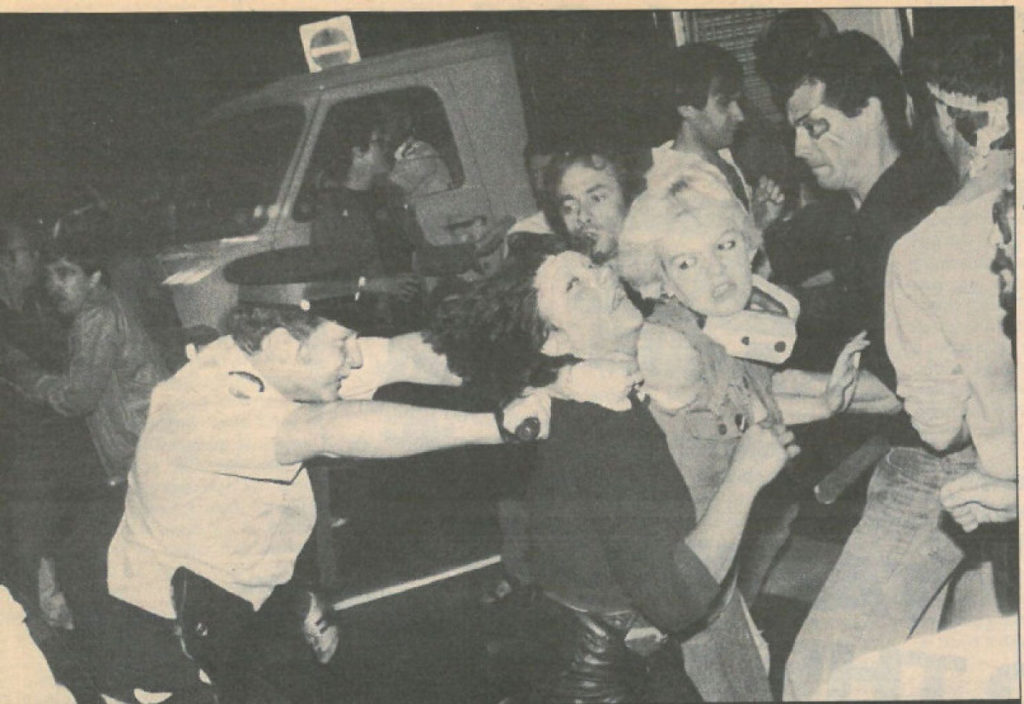

This is a place that I had visited on several occasions, as a 34 year old, out, gay man seeking to enjoy my newfound sexual freedoms in a supposedly safe space. But what happened that night was my first ever encounter with the State, and a police force that took it upon itself to enforce the archaic bawdy house laws that still exist to this day. We were rounded up that night, brutally. We were called dirty faggots and arrested as found-ins in a common bawdy house. The police may have suspected that money was being exchanged for sex, but this was never proven in court.

The premises were ransacked and several closed their doors, never to re-open. As you know and as [historian Tom Hooper] pointed out, the Prime Minister mentioned the bathhouse raids and Bawdy House law in his apology but to date we have seen no actions to back up his words, and as will also be pointed out by others, the bawdy house laws have also continued to be used against sex workers who continue to be criminalized in the spaces where they work under PCEPA (Protection of Communities of Exploited Persons Act), the new legislation.

So we were dragged through the courts that night. I was one of 35 people actually arrested and convicted out of the total number of 280 that night who were arrested. To this day, I have to say that it shocks me how traumatizing and stigmatizing the bathhouse raids prove to be. Often for people of different cultures who returned home that night, to their families, to their brothers, to their sisters, bearing in mind that at the time many people were engaging in activities that were not disclosed to their spouses or family.

I want to make the point that the unrelenting stigma of that evening continues to this day. It came as an even greater surprise to me to discover that there were remnants of records still, when we made an inquiry for information, residing with the Toronto Police Services. So I think it’s extremely important that Bill C-66 move beyond inclusion of those civil servants who were either fired and military personnel who were dishonourably discharged to include the expungement of records of those of us who were found-ins and arrested and convicted that night in the bathhouse raids. I think that is absolutely important and the right thing to do.

I do want to say though, that I don’t want our records totally lost forever and I do want to see them preserved for academics to use in the future. It’s important that we create some closure and important that we as a group be included in Bill C-66, or it will remain deeply flawed.

Angela Chiasson, Criminal Lawyers Association (speaking as an individual)

What I want to say today is that this piece of legislation, Bill C-66, is a backward looking piece of legislation. And given the historic nature of the apology, that’s perfectly appropriate. But let’s not just, today, look to past wrongs. Let’s also turn our mind to the current context. And that current context, unfortunately, is dismal.

Police services, at all levels, still target queer Canadians for arrest and criminal conviction. In 2017, for example, Toronto Police Services had an undercover sting operation that targeted spaces in which queer men were known to frequent. Those men were targeted and in my opinion, in some cases, entrapped by Toronto Police Services simply for being gay and bisexual men. That was the modus operandi of Toronto Police.

Now, what’s the tie-in with the current Bill? The bylaw infractions and criminal charges that were brought in this raid in 2017, were facially neutral, meaning that they apply equally to all Canadians. There’s a real danger of allowing police to use facially neutral laws to target queer Canadians. It lends the veneer of neutrality and it allows them some measure of protection from allegations of homophobia in their policing practices.

The tie-in with Bill C-66 is that Parliament only allows expungement for convictions of gross indecency or buggery, when in fact, the vast majority of convictions against queer Canadians have been facially neutral—they’ve been nudity, indecent theatre performances, and as my colleagues mentioned, being found in a common bawdy house. To not allow expungement in those cases, which is the vast majority of cases, is detrimental to this legislation, and it works against the object of the legislation, which is admirable. I sincerely hope that the Senate will consider the appropriate amendments to this Bill, and that includes broadening the sphere of criminal convictions which are available for expungement.