After the Fightback – Remobilizing labour and anti-capitalist resistance in the BC Liberal era

When Gordon Campbell was elected to the BC Premier’s office I was a young activist, and an anarchist more by disposition than ideological commitment. I had been a member of a few short-lived anti-poverty groups and occupied some welfare offices. What was new for me with the election of the BC Liberals was the feeling of a mass movement against poverty and class exploitation – there were suddenly workers in the streets, plowing the seas of class struggle and churning a wake where young radicals like me could make trouble.

The mass rallies against the BC Liberal agenda happened 10 years after the collapse of the Soviet communist parties, spelling the end of their occasionally militant influence in the BC Labour movement. But I remember the heady first days of the anti-Campbell struggle to be the last steps of the giant that had been the BC union movement and its related political tendency, social democracy. Now, 16 years later, I reflect on the end of social democracy not only as a setback, which it is because it represents the triumph of capitalist power, but also an opportunity to build a movement for working class and Indigenous power independent of both the Canadian state and its agents in the labour bureaucracy.

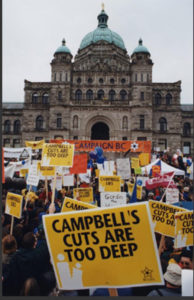

Campbell’s Cuts are too Deep

I was part of forming the Anti-Poverty Committee (APC) in December 2001 as a direct action “fightback” group, and we joined the broader BC Federation of Labour-led Communities Solidarity Coalition when it formed a month later. The politics of the Communities Solidarity Coalition were already marked by years of retreat before the rise of a new, high-finance dominated politics called neoliberalism.

It was not only a matter of the BC Liberals being in power. While the NDP held provincial office, they organized a retreat from social democratic, working class politics throughout the 1990s. The lowered expectations of these earlier years showed through the confidence of the 10,000 strong allied labour-community rallies against cuts to services and attacks on public sector unions, where unionists carried apologetic signs and banners reading “Campbell’s Cuts are too deep,” as though some cuts were okay, but not so fast and so crass. The problem, the NDP suggested, was the style rather than the principles of neoliberal social reorganization. And the implied solution was a different style, like that later promised by the NDP’s Carole James in the next election, which “require[d] a partnership, built on trust between government, labour, and the business community.”

Riding the wake of the unions

During the biggest Vancouver march organized by the Communities Solidarity Coalition, which focused on opposing Premier Campbell’s attack on teachers and hospital workers, I climbed the awning of the Woodward’s building and yelled through a megaphone at the crowd of thousands of trade unionists marching past, admonishing them to turn away from their mis-leadership and fight the Liberals and the NDP. Most waved back cheerfully while the labour marshalls fetched police to help get me down. There were also bright moments, like when thousands of unionists staged a solidarity marched from the BC Federation of Labour convention at Canada Place to the Woodward’s Squat.

But after those rallies produced the victory of COPE at Vancouver city hall, the labour leadership stopped calling their people out to the streets. Later, on the other side of Campbell’s defeat of the tremendous Hospital Employees Union strike in 2004 and the Teacher’s strike in 2005, labour turned away from low-income people and non-union workers. By the City election of 2014, even the once-relatively-radical Vancouver District Labour Council would not endorse or entertain motions against gentrification or for social housing. It was only then that I realized we radicals had been riding the labour movement’s wake and mistaking it for our own genius.

We are all Gordon Campbell now

The 15-year BC Liberal legacy is about more than right wing policies. It is not just tax cuts, market fundamentalist solutions to market problems, and a medicalized spin on the old cult of individual responsibility. The BC Liberal legacy is also the breaking of the independent political activity of the labour movement. It is the fragmentation of the left into single issue campaign groups that chase the different effects of a single, united Liberal offensive on all our different communities. It is the sense of despair and disappointment carried by so many lonely people who have withdrawn from social struggle.

Against this fragmentation and disappointment it is tempting to look back with nostalgia on the strengths of the labour unions of yesteryear. But I think the solution to this problem of the breakdown and neoliberalization of activism is not simply to go back to how things once were. The labour movement of old – even where it allowed for difference in its margins – is not something to be entirely mourned. It was a homogenizing force. It tended to treat class as an identity held by white men working in industry rather than a social process that sweeps all people who are not owners (or managers) into its hydraulic demands of constant production and constant growth. It also tended to side with Canadian imperial power against Indigenous peoples and their sovereignty. And all the critiques from the margins didn’t change its essence.

To purge the ghost of Gordon Campbell from our movements and ourselves, we should look towards engaging in the work that labour and the NDP has so far been uninterested in doing. Our first step is to analyze and organize the working class as a whole social body, as it actually is – waged and unwaged, unionized, temp, and unemployed worker – and align this class struggle with Indigenous movements fighting against Canadian state and settler power. Anti-capitalist and anti-colonial movements can rebuild our own social bases by recognizing working class and Indigenous community formations and struggles as they are and fighting like hell to be useful and accountable to them.