“We are too poor to afford anything” – new report uncovers the power of retail shops in the gentrification of Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside

Download the full pdf of this report here

Download the full pdf of this report here

In an area where over 13,000 people live in poverty having to survive on social assistance, gentrifying businesses are selling $138 mink eyelashes and $11 bottles of juice. Those are some of the findings of the Carnegie Community Action Project’s (CCAP) new retail gentrification report.

On Wednesday, February 22, CCAP released The Retail Gentrification Mapping Report, the result of a year-long project in which low-income residents surveyed over 450 retail stores in the neighbourhood.

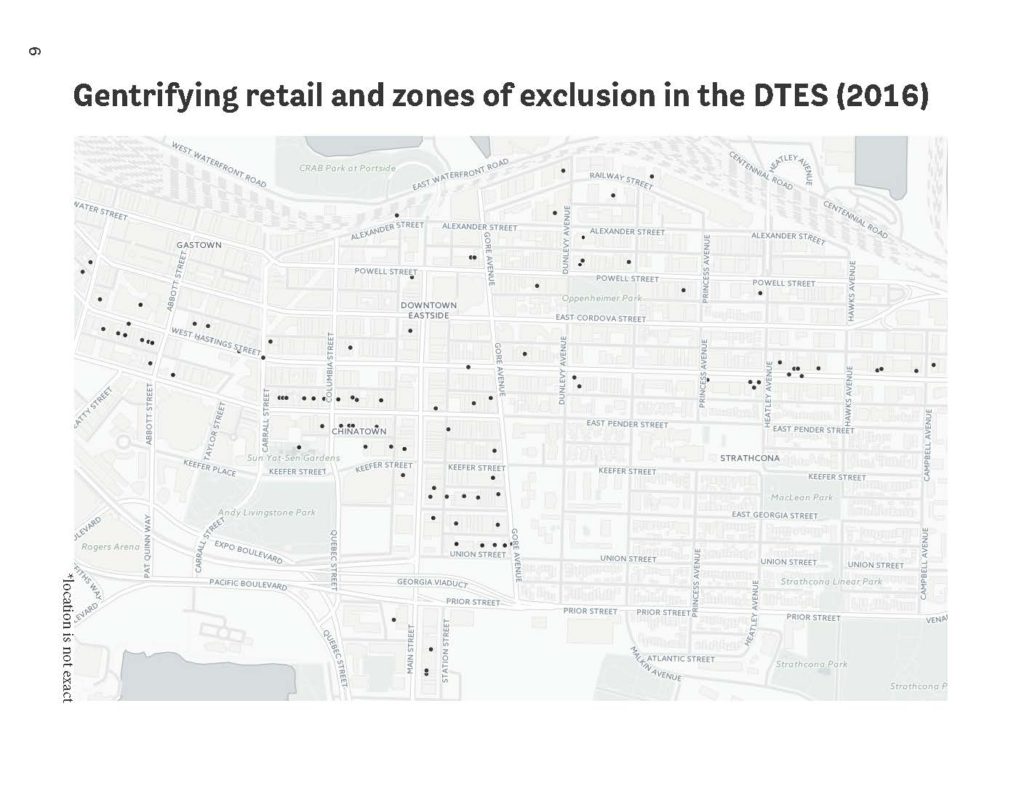

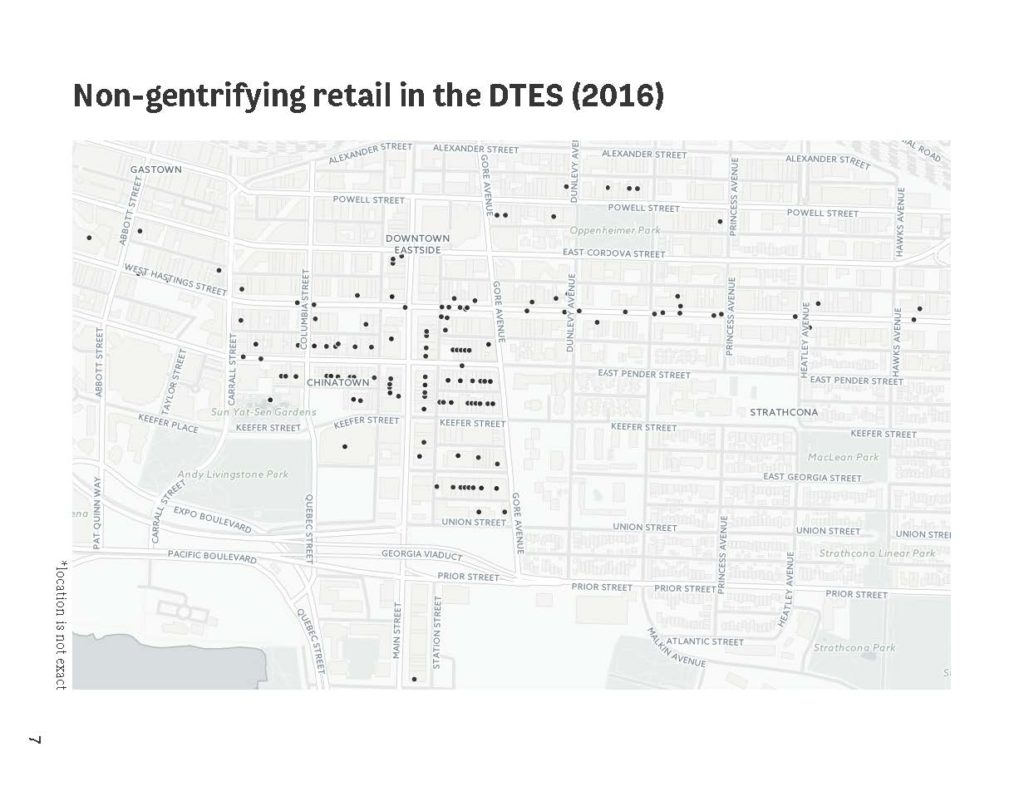

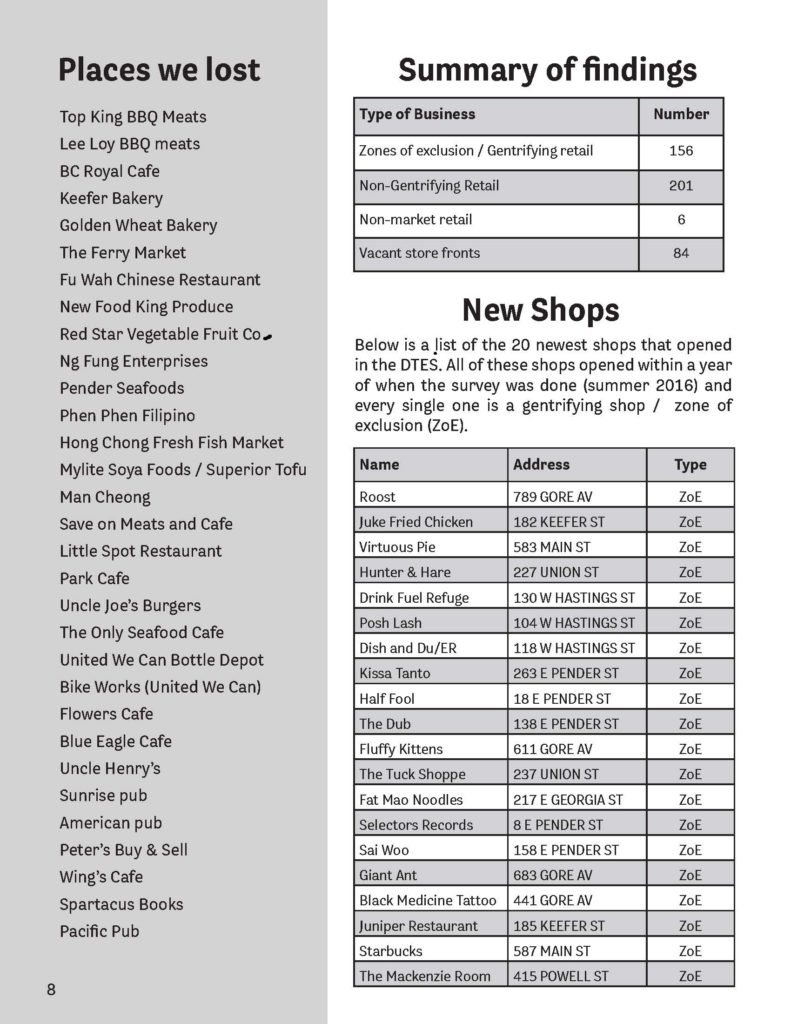

The report found that 20 new gentrifying/zone of exclusion businesses have opened since the summer of 2015. In total, there are now 156 gentrifying retail zones of exclusion businesses in the neighbourhood, which the report defines as retail stores that seek to attract and cater to higher income residents or visitors and exclude low-income community members.

CCAP and the Chinatown Concern Group held a press conference on Wednesday afternoon outside one of the new gentrifying businesses, Dalina, an upscale grocery and café in the heart of Chinatown. “What we found through the study was that there is no such thing as low income retail,” said Maria Wallstam, Coordinator at CCAP.

“If you are on social assistance, you’re too poor to afford anything at market rates.”

Erica Cynthia Grant, a member of the DTES community who suffers from lupus says she is no longer able to afford anything in the rapidly changing neighbourhood. She receives $800 in disability assistance with most of it going towards her $570-a-month rent, leaving very little for anything else. Without cooking facilities in SROs (Single Room Occupancy Units), she is unable to cook and relies on whatever food lineups are available and whatever food she can afford.

“When I don’t eat right, it really affects my daily living,” said Grant. “We won’t be able to afford a cup of coffee close to home let alone clothing or medical supplies.”

CCAP’s report says zones of exclusion are sites marked by increased surveillance and policing where only those with status, privilege, and wealth are welcome while others are criminalized.

“When we come to any one of these restaurants or shops, security guards follow us like we are going to steal. We are not down here trying to steal stuff, we are just trying to get what we need,” said Grant.

Mrs. Luu, a resident of Chinatown for over 30 years, also spoke about retail gentrification in Chinatown at the press conference. “Over these past few decades, I’ve seen all the changes. One after another, all these shops are closing,” said Mrs. Luu, through translator and Chinatown Concern Group Coordinator, Beverly Ho. “A lot of the Chinese shops like Lee Loy BBQ meats have moved. Where will we buy groceries in a few years if this keeps happening?”

The Retail Gentrification Mapping report includes several recommendations such as addressing the root causes of poverty, implementing measures to stop new zones of exclusion, reversing the loss of shops that cater to low-income residents, stopping the criminalization of poverty and all survival work, expanding and supporting nonmarket food services in the DTES, and ensuring jobs for low income-residents.

The Retail Gentrification Mapping report includes several recommendations such as addressing the root causes of poverty, implementing measures to stop new zones of exclusion, reversing the loss of shops that cater to low-income residents, stopping the criminalization of poverty and all survival work, expanding and supporting nonmarket food services in the DTES, and ensuring jobs for low income-residents.

“We need higher welfare rates. We need housing,” said Wallstam. “How are you supposed to get a job if you’re staying in a shelter?”

“Most of the city’s community economic development strategy is focused on bringing market retail into the DTES,” continued Wallstam. “But what we know down here is that market retail doesn’t help low-income people. These new shops are not welcoming to low-income people and they are displacing the shops that serve the low-income community. Retail gentrification is also increasing land values, pushing up rents in SRO Hotels and forcing low-income people onto the streets.”

“We are too poor to afford anything”

The initial goal of the project was to identify retail that caters to the low-income community. However, we quickly realized while doing the survey that even the businesses that are more affordable and welcoming to low-income people do not really meet the needs of people on social assistance. The answer to the question “Can you afford anything in this shop?” was 9 out of 10 times: “No, only on cheque day.”

The BC government provides $610 a month in welfare to a single person, without a recognized disability, who is expected to look for work. It has been at this level since April 2007. Once rent and other essentials are paid for, a person on welfare has $76 left to spend on food for a whole month. This means that a person on welfare has only $18 (at most) to spend on food each week. This also means that even if a shop is relatively affordable (and also welcoming to low-income residents), a person on welfare can hardly afford to buy anything at market rates. Instead, people on welfare and disability have to rely on non-market or free sources for food, such as food line-ups, Union Gospel Mission, the Evelyn Sellar and the Carnegie.

Gentrification produces zones of exclusion

Gentrification produces zones of exclusion

Gentrification not only forces people out of the neighbourhood through increasing land value and higher rents, it also produces a kind of internal displacement for low-income residents by creating zones of exclusion.

Zones of exclusion are spaces where people are unable to enter because they lack the necessary economic means for participation. As wealthier people move into the neighbourhood, more spaces are devoted to offering amenities that cater to them.

Grocery stores, banks, coffee shops, restaurants, salons, various retail stores, night clubs, stylish pubs, etc. begin to appear throughout the neighbourhood, and are priced beyond what people on fixed income can afford. These sites become zones of exclusion.

Zones of exclusion also become sites marked by increased surveillance and policing. Strategies of control and punishment are implemented at these sites in order to protect them from the presence of unwanted people and from potential disruption.

Only those with status, privilege and wealth can enter; all others are watched, interrogated, and criminalized.

There is another sense in which such places are zones of exclusion. Whenever land is used to build condos or develop businesses for wealthier people, it is removed or excluded from use by the community; it not longer becomes a place where a local community-based vision can be implemented. In this sense, gentrification excludes possibilities.

*This article was originally published in the Carnegie Community Action Project Newsletter. Download the full pdf of CCAP’s Retail Gentrification report here.