Remembering Art Manuel, leader of an intergenerational struggle to unsettle Canada

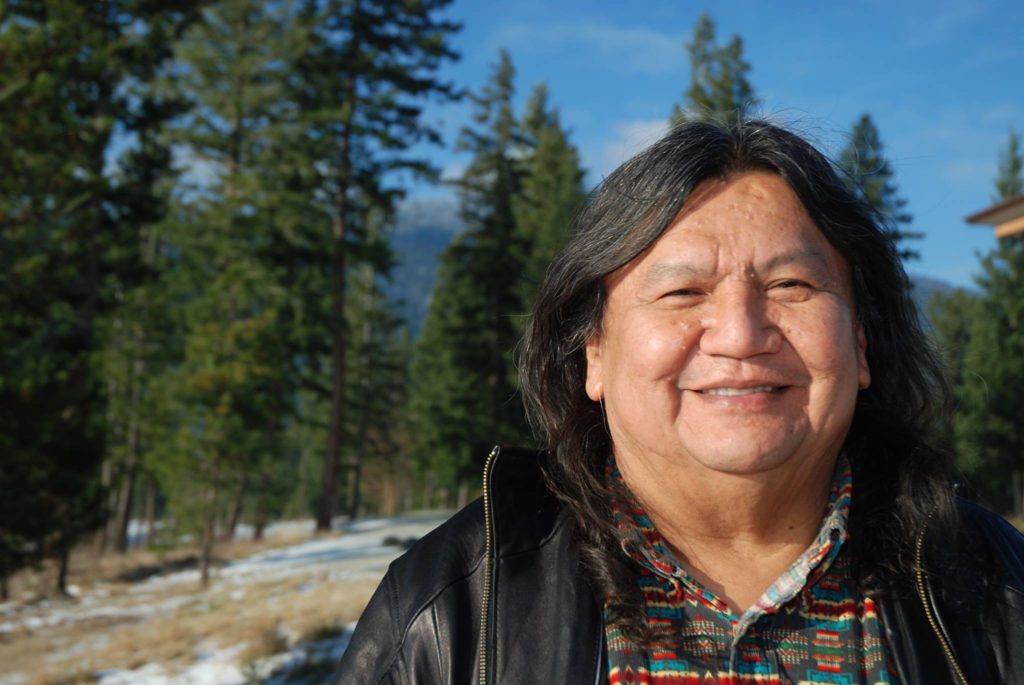

Art Manuel, former Chief of the Neskonlith band of the Secwepemc nation, and lifelong fighter for Indigenous sovereignty, died unexpectedly in early January at the age of 66. As a tribute to Art we are publishing an excerpt of one of many talks and selections from his book presented at his Vancouver memorial service.

As long as I’ve been an adult and conscious as an Indigenous activist, Art has always been there. I didn’t know him as well as a lot of people in this room, but he had a huge impact on me and I learned a lot from him. Some of the things I learned from him were the importance of understanding Canadian law. A lot of the things I now take for granted, the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British North America Act, understanding the dangers of Fee Simple property on reserve lands– these tools of Canadian law that have been used to dispossess us, I learned them from him originally. In understanding out struggles as Indigenous people and land, Art showed us that we need to think beyond reserves. It’s now something I take for granted but it was something I learned from Art.

Something else I learned from Art was understanding our struggles intergenerationally. In his writings and when he spoke, he referred to people in his family who he learned from as his legacies. In my own family, intergenerational refers to trauma and the hard things that we draw from, but there’s also that strength. It didn’t really occur to me until I became a parent myself that intergenerational also means my relationship with my son, what I pass down to him, what I teach him. In that process of passing things down to him I realize the things that I’m still learning.

One of the things that strikes me about when I met Art, was that it was a process of meeting his entire family through the years. I can’t remember if it was his daughters I met first or him. It’s a wonderful thing that Art was intergenerational as a presence.

I’m going to read from his book when he’s talking about the Secwepemc struggle at the beginning of the 2000s to protect the Skwelkwek’welt alpine territory from the expansion of the Sun Peaks ski resort.

Sun Peaks to Geneva: Playgrounds and Fortresses

Janice Billy, an activist in our community who was then working on her doctorate in education, informed me that the Elders and youth had gotten together to put up a small protest camp in Skwelkwek’welt. The action fit with the strategy of proving our title on the ground, and I instantly supported it. […] Our people then set up the Skwelkwek’welt Protection Centre at the entrance of Sun Peaks ski resort to monitor environmental damage, to inform visitors and investors of the ongoing unresolved land issue, and to assert their title and rights to unceded lands.

Over the next several year, five Skwelkwek’welt Protection Centres, two traditional cedar bark homes, a hunting cabin, two sacred sweat lodges, and one cordwood house – home to a young Secwepemc family – were bulldozed or burned down by the resort or by persons unknown. None of these acts were investigated by the police, who, we noticed, were increasingly acting like hired security guards for the resort.

[T]he BC government and Sun Peaks redoubled their efforts to isolate the youth and Elders at the Protection Centre and increased the use of police to put pressure on them. At the same time, they launched a Gustafsen Lake-style smear campaign against the protesters, impugning their intelligence and their sanity and whipping up the latent racism against our people in the region.

By this time, the tensions were not only with the white community, but also within our own. In Neskonlith, and even more so in other Secwepemc communities, people began to have a genuine fear of white backlash and government reprisals. This last fear was felt more acutely by the chiefs. They were in the business of delivering government programs and services, and it is at moments like this that our dependency becomes most evident. Some understand that the only way out is to break that dependency once and for all, to assert our right to our lands and begin to build true Indigenous economies on our territories.