Lessons about “community inclusion” from the DTES Local Area Planning Process

In 2014, the city of Vancouver approved a new Local Area Plan (LAPP) for the Downtown Eastside after four bitter years of consultation. Low-income community groups tend to view the LAPP as a failure as it continues to displace their vulnerable community. Low-income people participated in the process but they were drowned out. Other groups, like Japanese Canadians, wanted to help build a socially just community, but were mostly ignored.

Before the LAPP even started there were discussions between the city, low-income activists and others. It was agreed the purpose of the LAPP was to “improve the lives of those that live in the area, low-income and vulnerable people in particular.” Although the LAPP was proposed as a “partnership among participants” everything that the low-income community wanted had to go through the city manager and city council, meaning those peoples’ ideas could be translated to fit the city’s ideas. The term for this is tokenism. Outspoken low-income activists like Ivan Drury and Herb Varley got kicked of the committee when their voices became too strong or the city didn’t like what they were saying. One of the people interviewed about the LAPP said “it’s clear that we aren’t making decisions… they were coming from the top.”

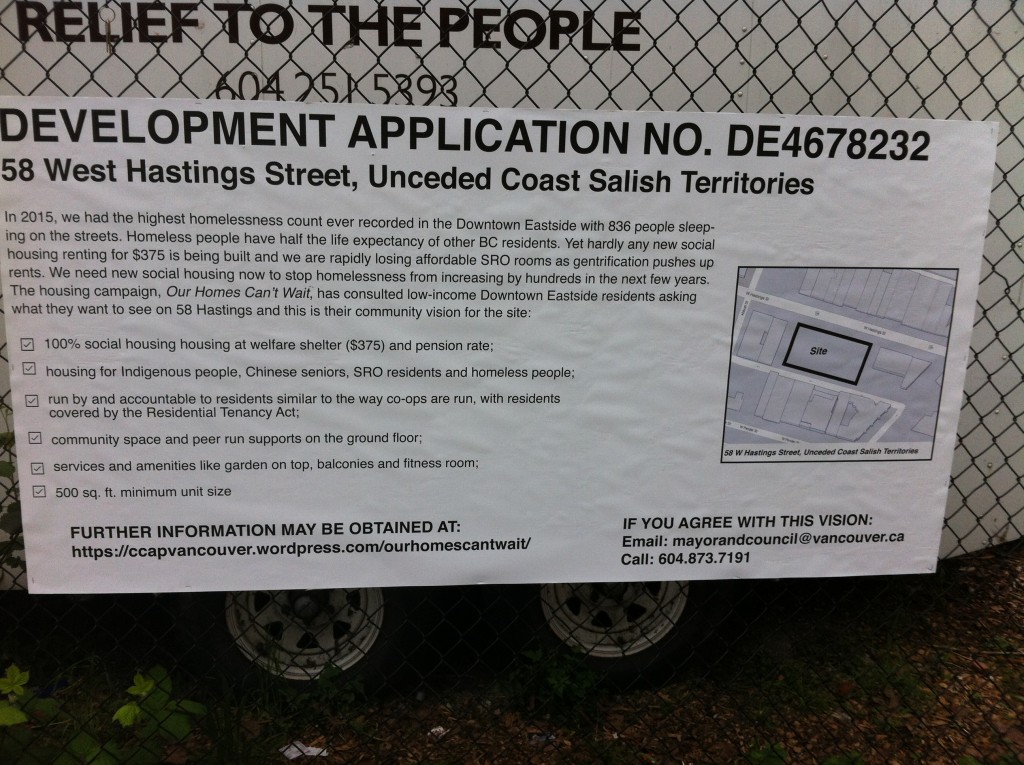

The LAPP redefined the DTES as a “community of communities” including, Gastown, Chinatown, and Strathcona erasing an important low-income claim to the neighborhood. As the LAPP went on, the city designated the DTES Oppenheimer District (DEOD – the area with the highest ratio of low-income residents), a “Community Based Development Area” (CBDA). This did two important and seemingly contradictory things. First, it created a space where the low-income people could “be.” Second it made room for “local economic development” and “revitalization” (gentrification) in the poorest area of the DTES. The wealthier parts of the area like Strathcona and Gastown were not changed through planning as their neighbourhoods just rolled their own plans into the LAPP. A planner said “the major change to policy is in the DEOD.”

The city distorted the input of the Japanese Canadian community

The city wanted to plan an area that they could control more easily. They distorted other people’s words too. The Japanese Canadian community (who were uprooted from the area in World War 2) were involved in the LAPP, many of them (particularly the Powell Street Festival Advocacy Committee) were interested in supporting the low-income community. Japanese Canadians saw parallels in how the low-income community were being displaced from their homes in the DTES. They told the city not to use their heritage in any way to gentrify the neighborhood. The city ignored this and created an ideal “Japantown” near Oppenheimer Park. This was to be used as a shopping area, not as a place with social housing and services for low-income people. Powell Street is important to Japanese Canadians; it is also the living room for low-income communities. The City’s idea of “Japantown” perverts Japanese Canadian history in ways that can be used to displace low-income people. This is highly ironic as new evidence shows that Vancouver politicians and planners in the 40’s made the uprooting of the Japanese Canadians possible.

Did anything good come of the LAPP?

Although the LAPP turned out badly for the people it claimed to help, it led to some important alliances between the low-income community and Japanese Canadians. One participant stated “The Japanese Canadian community was good at establishing comradeship. It’s a huge plus for the low-income activists to know that.” An important moment happened after the LAPP ended, during the tent city of 2014. The Powell Street festival celebrating Japanese Canadian culture was supposed to have the park at the same time. Instead of telling the tent city to clear the space the festival moved and supported the right of residents to stay. Although the tent city was eventually shut down people have since rallied around the Right to Remain, and are standing up for their rights in the face of potential displacement. So while the LAPP tried to take power away from low-income people in the DTES, alliances now exist between activists who are concerned with people’s history and dignity rather than making the DTES safe for property-led economic development.